Primer: ACI 318-19 Chapter 17 Concrete Anchorage Design

“Primers” are my personal notes on various technical topics in structural engineering. Building codes are dense and voluminous, sometimes written in legalese rather than in sentences that can be easily understood. I write these “Primer” so I can gather, organize, and condense technical topics I encounter as an engineer. Please understand I made these for myself. Reader discretion is advised. No warranty is expressed or implied by me on the validity of the information presented herein.

- 1.0 Fundamentals

- 2.0 ACI 318-19 Design Criteria

- 3.0 Tensile Strength

- 4.0 Shear Strength

- 5.0 Shear Lugs

1.0 Fundamentals

The topic of concrete anchorage is guided entirely by experimental testing, much of which can be attributed to University of Stuttgart. Because of its empirical nature, there seems to be an overabundance of variables and factors that can simply be overwhelming for first-time users. The good thing about this is that all of the complexities of concrete anchorage mechanics has been abstracted away into empirical factors, leaving only the concepts that are essential and fairly intuitive to understand. Nevertheless, if you ever want to do a deep dive into where these factors came from, there is an excellent textbook by Dr. R Eligehausen, R Mallee, and J Silva that summarizes decades of research and is surprisingly readable. [Amazon Link Here]

ACI 318-19 covers the topic of concrete anchorage fairly comprehensively in Chapter 17. Truth of the matter is, anchorage calculation is very tedious. Furthermore, because of the abundance of empirical factors, and the plethora of code requirements, in practice, it is more common to use anchor design softwares like HILTI PROFIS. The intent of this article is to give a primer, in the most concise manner possible, to someone who wish to understand concrete anchorage rather than relying on third-party softwares.

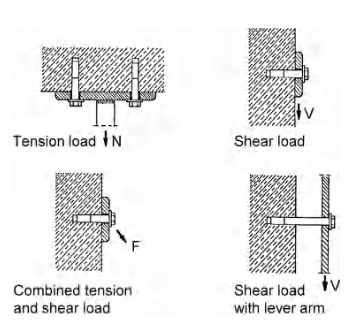

Fundamentally, demand on an anchor can ultimately be separated into either tension or shear. Moments can be resolved locally into axial force couples which induces additional tension on the anchors. Torque, which is just moment applied about an axis out-of plane to the fixure plate, induces additional shear. In practice, analysis of shear and tension is done separately, and then combined in the end using various T+V interaction equations.

- Tension

- Shear Load (Without Lever Arm)

- Shear Load (With Lever Arm)

- Combined Shear + Tension

Figure 1: Anchorage Actions

Figure 1: Anchorage Actions

Technically, an anchor can also be placed into bending by a standoff. This is not explicitly covered in ACI 318-19, but they do exist in things like cladding attachments, or base plate with large grout layer that may spall. The European code does address shear with lever arm in ETAG-001 Annex C and I’ll include the relevant sections in this article.

The anchor types can be separated into 3 groups:

- Cast-In-Place Anchors

- Post-Installed Expansion Anchors

- Post-Installed Adhesive Anchors

Cast-in-place anchors rely on mechanical interlock, expansion anchors rely on friction induced by a wedge at the tip of the anchor, and epoxy anchors rely on bond or chemical interlock. Furthermore, as their name implies, installation occurs at different stage of construction. Post-installed expansion anchors seem to be a contractor favorite as they are easy to install and require no coordination before concrete pour.

2.0 ACI 318-19 Design Criteria

17.5.2 - Similar to the rest of ACI 318-19, all concrete anchorage calculations are in LRFD. Capacity and demand associated with tension is denoted with letter “N”, capacity and demand associated with shear is denoted with letter “V”. In both cases, they represent the lowest capacity

\[\phi N > N_{ua} \tag 1\] \[\phi V > V_{ua} \tag 2\]R17.8.3 - The general procedure for any anchorage design is to analyze all the various failure modes associated with shear and tension separately to get the governing (lowest) capacity, and then combine together in the form of an interaction equation.

\[(\frac{N_{ua}}{\phi N_n})^{5/3} + (\frac{V_{ua}}{\phi V_n})^{5/3} <1.0 \tag 3\]There are a whole lot of subscripts and combination of subscripts appended to the two variables above. Here is a comprehensive list:

Demand:

- \(N_{ua} \mbox{ or } N_{ua,i}\) = tension demand of single anchor

- \(N_{ua,g}\) = tension demand of anchor group

- \(V_{ua} \mbox{ or } V_{ua,i}\) = shear demand of single anchor

- \(V_{ua,g}\) = shear demand of anchor group

Capacities:

- \(N_{sa}\) = steel tensile strength

- \(N_{cb}\) = concrete tension breakout strength

- \(N_{cbg}\) = concrete tension breakout strength (anchor group)

- \(N_{pn}\) = anchor tension pullout

- \(N_{sb}\) = concrete side-face breakout strength in tension

- \(N_{a}\) = Tensile bond strength of adhesive anchor

- \(V_{sa}\) = steel shear strength

- \(V_{cb}\) = concrete shear breakout strength

- \(V_{cbg}\) = concrete shear breakout strength (anchor group)

- \(V_{cp}\) = concrete shear pryout strength

- \(V_{cpg}\) = concrete shear pryout strength (anchor group)

Factors:

- \(\Psi_{ec,N}\) = tension breakout eccentricity factor (17.6.2.3)

- \(\Psi_{ed,N}\) = tension breakout edge distance factor (17.6.2.4)

- \(\Psi_{c,N}\) = tension breakout cracking factor (17.6.2.5)

- \(\Psi_{cp,N}\) = tension breakout splitting factor (17.6.2.6)

- \(\Psi_{c,P}\) = pullout cracking factor (17.6.3.3)

- \(\Psi_{ec,Na}\) = bond eccentricity factor (17.6.5.3)

- \(\Psi_{ed,Na}\) = bond edge factor (17.6.5.4)

- \(\Psi_{cp,Na}\) = bond splitting factor (17.6.5.5)

- \(\Psi_{ec,V}\) = shear breakout eccentricity factor (17.7.2.3)

- \(\Psi_{ed,V}\) = shear breakout edge distance factor (17.7.2.4)

- \(\Psi_{c,V}\) = shear breakout cracking factor (17.7.2.5)

- \(\Psi_{h,V}\) = shear breakout thickness factor (17.7.2.6)

17.5.3 - Resistance factors (\(\phi\)) are listed below.

- Steel Tension Failure

- \(\phi = 0.75\): Ductile steel (more common)

- \(\phi = 0.65\): Brittle steel

- Steel Shear Failure

- \(\phi = 0.65\): Ductile steel (more common)

- \(\phi = 0.60\): Brittle steel

- Tension Breakout, Bond, Side-Face Blow Out

- \(\phi = 0.70\): for cast-in anchors

- \(\phi = 0.75\): for cast-in anchors w/ anchor reinforcement

- \(\phi = 0.65\): for post-installed anchors (Category 1*). No supp. reinf.

- \(\phi = 0.55\): for post-installed anchors (Category 2*). No supp. reinf.

- \(\phi = 0.45\): for post-installed anchors (Category 3*). No supp. reinf.

- Increase factor for post-installed anchor by 0.1 if supp. reinf. is present

- Shear Breakout

- \(\phi = 0.75\): shear breakout w/ anchor reinforcement

- \(\phi = 0.70\): all other cases

- Anchor Tension Pullout

- \(\phi = 0.70\): for cast-in anchors

- \(\phi = 0.65\): for post-installed anchors (Category 1*)

- \(\phi = 0.55\): for post-installed anchors (Category 2*)

- \(\phi = 0.45\): for post-installed anchors (Category 3*)

- Shear Pryout

- \(\phi = 0.7\): All cases

- Shear Lugs

- \(\phi = 0.65\): Bearing and breakout

*Note that anchor categories are defined in ACI 355.2 or ACI 355.4. The anchor manufacturer usually provides the appropriate category of their anchors. Category 1 indicates high reliability. Category 2 indicates medium reliability. Category 3 indicates low reliability.

*Supplementary reinforcement refers to any reinforcement within the concrete that is preventing splitting cracks. It does not need to be explicitly designed.

17.2.1 - Shear and tension demand is calculated with an elastic analysis. Where more rigor is required, a plastic analysis is also permitted.

17.3.1 - Due to lack of available test data, \(f'_c\) for calculation purposes cannot exceed 10 ksi for cast-in-place anchors, and 8 ksi for post-installed anchors.

17.10.5.3 - For seismic applications, all concrete anchorage must be design for \(\Omega\) level forces (2x to 3x amplification). There are ways to avoid this by doing some more rigorous detailing and design (see code clause), but the common practice is to just amplify anchorage demand by \(\Omega_o\) (see ASCE 7-16).

\[E_h = \Omega_o E \tag 4\]17.10.5.4 - For seismic applications, concrete should be assumed to be cracked unless demonstrated otherwise. In addition, the following tension capacities must be reduced by 25%.

- Reduce tension breakout capacity (\(0.75 \phi N_{cb} \mbox{ and }0.75 \phi N_{cbg}\)) - does not apply if breakout resisted by anchor reinforcement

- Reduce anchor pullout capacity (\(0.75 \phi N_{pn}\))

- Reduce tension side-face breakout capacity (\(0.75 \phi N_{sb} \mbox{ and }0.75 \phi N_{sbg}\))

- Reduce anchor bond capacity (\(0.75 \phi N_{a} \mbox{ and }0.75 \phi N_{ag}\))

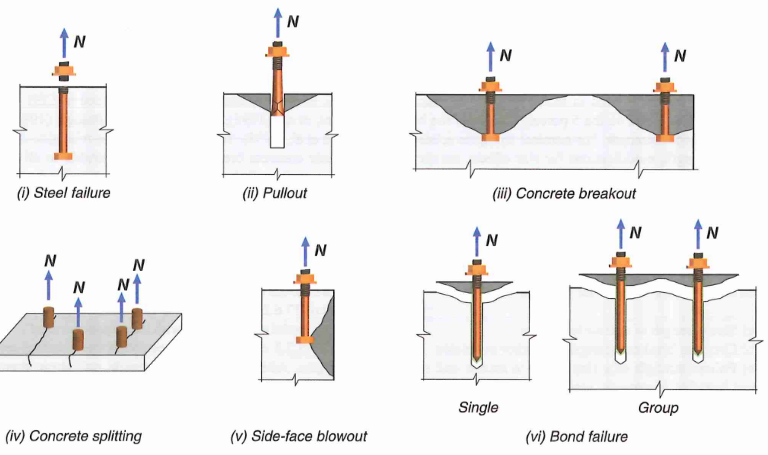

3.0 Tensile Strength

Figure 2: Anchor Tension Failure Modes

Figure 2: Anchor Tension Failure Modes

3.1 Failure Mode - 1 Steel Failure

17.6.1.1 - Nominal steel strength of anchor in tension is calculated as follows:

\[N_{sa} = A_{se,N} f_{uta} \tag 5\]where:

- \(f_{uta}\) = ultimate steel rupture strength (Fu) and shall not exceed 1.9Fy or 125 ksi

- \(A_{se,N}\) = net cross section area in threaded region of anchor that is usually in the range of 0.7 to 0.9Ag (typically provided by manufacturer). If threaded area is not given, it can be calculated per ASME B1.1 as follows.

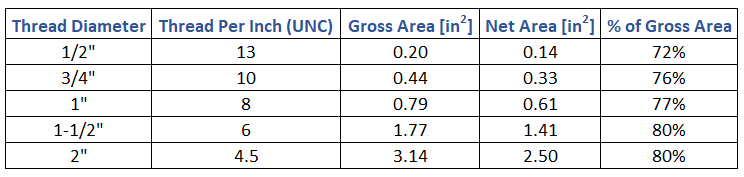

nt is the number of thread per inch. Thread geometry for unified coarse (UNC) can be found online. Example

Table 1: Net Area of Threaded Section Estimation per UNC

Table 1: Net Area of Threaded Section Estimation per UNC

Alternatively, follow the AISC 360 provisions and use gross area along with a reduced material strength.

3.2 Failure Mode 2 - Anchor Pullout

Pullout is calculated as the force at the onset of local concrete crushing at the bearing end of the anchor head. This is thought to be the beginning of a pullout failure because of the rapid decrease in stiffness afterwards. In other words, pullout capacity is purely a function of end bearing area, and is not related to embedment length (friction neglected).

17.6.3.2.1 - Pullout mechanism for expansion anchors, screws, and undercut anchors are fundamentally different and cannot be calculated per ACI 318. Instead, refer to manufacturer ESR report for suggested pullout strength.

17.6.3.2.2 - For cast-in headed studs or bolts:

\[N_{pn} = \Psi_{c,p} \times 8A_{brg}f'_c \tag 7\]17.6.3.2.2 - For hooked ends anchors

\[N_{pn} = \Psi_{c,p} \times 0.9f'_c e_h d_a \tag 8\]- \(A_{brg}\) is the net bearing area of the headed stud

- \(e_h\) is distance from inner surface of shaft to tip of J or L-bolt. Must be between \(3d_a\) and \(4.5d_a\)

- \(d_a\) is the diameter of anchor

- \(\Psi_{c,p}\) is the pullout cracking factor. Use 1.0 for cracked concrete (almost always), use 1.4 for uncracked concrete.

17.10.5.4 - For seismic application, reduce anchor capacity in pullout by 25%

\[0.75 \phi N_{pn} \tag 9\]3.3 Failure Mode 3 - Concrete Breakout

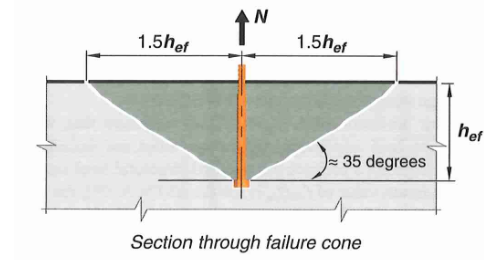

Figure 3: Concrete Tension Breakout Failure Cone

Figure 3: Concrete Tension Breakout Failure Cone

17.6.2.1a - For a single anchor:

\[N_{cb} = N_b \times ( \frac{A_{Nc}}{A_{Nco}} ) ( \Psi_{ed,N} \Psi_{c,N} \Psi_{cp,N}) \tag {10}\]17.6.2.1b - For an anchor group:

\[N_{cbg} = N_b \times (\frac{A_{Nc}}{A_{Nco}}) (\Psi_{ec,N} \Psi_{ed,N} \Psi_{c,N} \Psi_{cp,N}) \tag {11}\]That is a lot of variables. Let’s go through them one by one.

17.6.2.2 - Basic single anchor breakout capacity

This is the basic concrete breakout strength, of a single anchor, in cracked concrete. We will use this value as a starting point and apply several modification factors for other conditions.

\[N_{b} = k_c \lambda_a \sqrt{f'_c} h_{ef}^{1.5} \tag {12}\]where:

- \(h_{ef}\) = embedment depth

- \(k_c\) = 24 for cast-in anchors, and 17 for post-installed anchors (may be increased if proven by manufacturer)

ACI also permits a slightly less conservative equation for anchors embedded between 11 in to 25 in (17.6.2.2.3), however it becomes unconservative beyond 25 inch; making it only applicable for anchors embedded between 11” to 25”. For simplicity, it is convenient to just use equation 12 above. But it is good to know that you can perhaps squeeze out 10 to 30 kips.

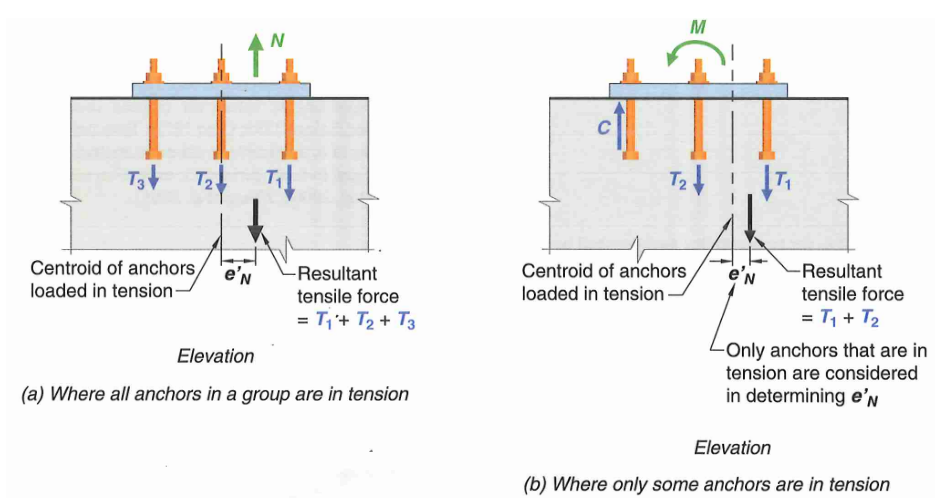

17.6.2.3 - Breakout Eccentricity Factor (\(\Psi_{ec,N}\))

This factor is unique to anchor groups. If the resultant tension on an anchor group is concentric, or if we are looking at a single anchor:

\[\Psi_{ec,N} = 1.0 \tag {13}\]On the other hand, when a moment is applied to an anchor group, the resultant tension is not concentric meaning some anchors are more stressed in tension than others.

\[\Psi_{ec,N} = \frac{1}{1+\frac{e'_N}{1.5h_{ef}}} <=1.0 \tag {14}\]\(e_N\) is the distance from centroid of anchor loaded in tension to the resultant tensile force.

Figure 4: Anchor Tension Eccentricity Factors

Figure 4: Anchor Tension Eccentricity Factors

17.6.2.4 - Breakout Edge Effect Factor (\(\Psi_{ed,N}\))

If the minimum edge distance is at least \(1.5h_{ef}\), then a full breakout cone can form and no edge reduction factor is necessary.

\[\Psi_{ed,N} = 1.0 \tag {15}\]Otherwise, if the anchor or anchor group is close to an edge:

\[\Psi_{ed,N} = 0.7 + 0.3 \frac{ c_{a,min} }{ 1.5h_{ef} } \tag {16}\]\(c_{a,min}\) is the minimum edge distance.

17.6.2.1.2 - If there are 3 or more edges (less than \(1.5h_{ef}\)), such as at the end of a narrow grade beam, the effective embedment must also be reduced in all equations that involve embedment depth.

\[h_{ef} = max( c_{a,max}/1.5, s/3) \tag {17}\]where “s” is the maximum spacing between anchors, and \(c_{a,max}\) is the maximum edge distance that is less than \(1.5h_{ef}\)

17.6.2.5 - Breakout Cracking Factor (\(\Psi_{c,N}\))

Modification factor for cracking. Typically assume all concrete are cracked for conservatism unless more rigor is required. Cracked concrete has a modification factor of 1.0.

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.0\) for cracked condition (most commonly used)

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.25\) for cast-in anchors (uncracked)

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.4\) for post-installed anchors (uncracked). Or use value from manufacturer ESR report.

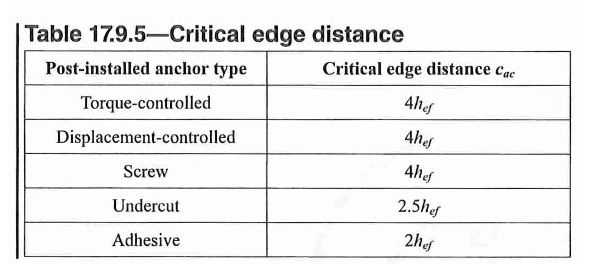

17.6.2.6 - Breakout Splitting Factor (\(\Psi_{cp,N}\))

For cast-in anchors, or any anchors designed for cracked concrete, the splitting factor can be taken as 1.0. Since we will mostly be assuming cracked concrete, this will be the case.

\[\Psi_{cp,N} = 1.0 \tag {18}\]For post-installed anchors designed for uncracked condition:

- \(\Psi_{cp,N} = 1.0\) if the critical edge spacing \(c_{ac}\) is met. Otherwise:

The critical edge spacing \(c_{ac}\) is required for post-installed anchors installed to uncracked condition without anchor reinforcement to prevent splitting cracks.

Table 2: Anchor Critical Edge Distance for Splitting Failure

Table 2: Anchor Critical Edge Distance for Splitting Failure

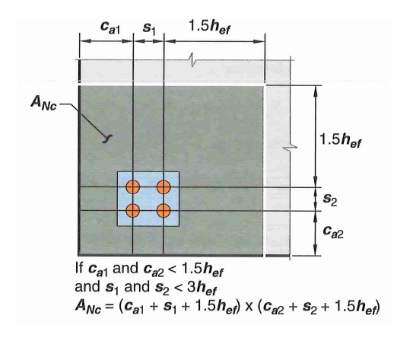

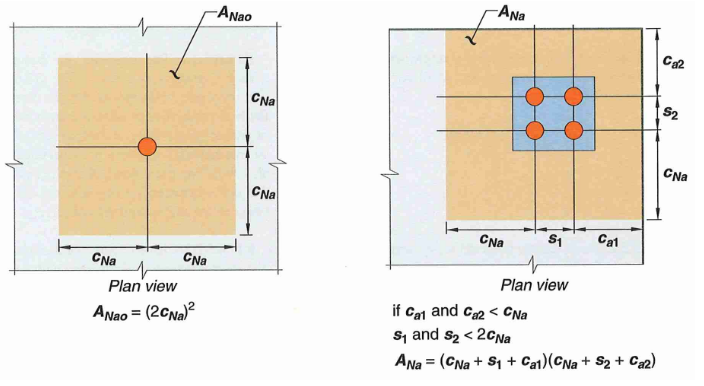

17.6.2.1.4 - Full Projected Failure Area of Single Anchor (\(A_{Nco}\))

Based on a 35 degree breakout cone, the projected failure area is a square with side length of \(2 \times 1.5h_{ef}\) (see figure 3). Note that the failure area is taken as a rectangle rather than an ellipse for simplicity.

\[A_{Nco} = 9h_{ef}^2 \tag {20}\]17.6.2.1.1 - Actual Projected Concrete Failure Area (\(A_{Nc}\))

The actual breakout area must be adjusted.

For anchor group with 1 or 2 edges, this can be represented in equation form as:

\[A_{Nc} = (1.5h_{ef}+s_1+c_{a1}) \times (1.5h_{ef}+s_2+c_{a2}) \tag {21}\]However, the projected area must not exceed \((n A_{nco})\) where n is the number of anchor in the anchor group. \(c_{a1}\) is taken as the minimum edge distance.

For anchor group with 3 or more edges, effective embedment depth has to be reduced per 17.6.2.1.2. See figure below for example breakout area calculation. In essence, the breakout cone will extend \(1.5h_{ef}\) orthogonally beyond the outermost anchor unless interrupted by an edge.

Figure 5: Concrete Breakout Area Example

Figure 5: Concrete Breakout Area Example

17.10.5.4 - For seismic application, reduce tension breakout capacity by 25%

\[0.75 \phi N_{cb} \tag {22}\]3.4 Failure Mode 4 - Concrete Splitting

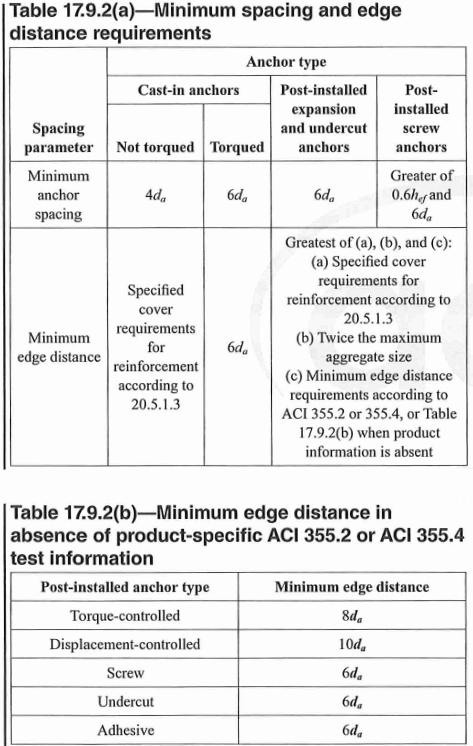

There is no capacity to calculate for concrete splitting failure. Instead, ACI 318 forces specific detailing requirements to preclude the possibility of splitting failure. Also most manufacturer ESR report will have these information. Here are some of the most important ones:

17.9.5 - minimum edge distance for post-installed anchor (shown above in table 2)

17.9.4 - effective embedment of post-installed anchors should not exceed 2/3 of slab depth to prevent blowout on the opposite side. For example, in a 12” slab, the embedment should not be greater than 8”. Note this does not apply to epoxy or cast-in anchors.

17.9.2 - in general, try to have spacing of at least \(6d_b\) and edge distance at least \(8d_b\)

Table 3: Splitting Failure Spacing and Edge Distance Requirements

Table 3: Splitting Failure Spacing and Edge Distance Requirements

3.5 Failure Mode 5 - Side Face Blowout

This failure mode is only applicable for anchors near an edge.

17.6.4.1 - For single headed anchor with \(h_{ef} > 2.5 c_{a1}\):

\[N_{sb} = 160 c_{a1} \sqrt{A_{brg}} \lambda_a \sqrt{f'_c} \tag {23}\]17.6.4.1.1 - if \(c_{a2} < 3c_{a1}\), then multiply the above equation by the factor:

\[0.25(1+ \frac{c_{a2}}{c_{a1}}) \tag {24}\]- \(A_{brg}\) is the net bearing area of the headed stud

- \(c_{a1}\) is the edge distance in the direction of applied shear. If no shear is applied, use the minimum edge distance

- \(c_{a2}\) is the edge distance perpendicular to \(c_{a1}\)

- In equation 24, \(\frac{c_{a2}}{c_{a1}}\) should be between 1.0 to 3.0

17.6.4.2 - For head anchor group with \(h_{ef} > 2.5 c_{a1}\) and anchor spacing along the edge \(s< 6c_{a1}\):

\[N_{sbg} = (1+ \frac{s}{6c_{a1}}) N_{sb} \tag {25}\]Only the anchors close to the edge (\(c_{a1}<0.4h_{ef}\)) should be considered.

17.10.5.4 - For seismic application, reduce side face blowout capacity by 25%

\[0.75 \phi N_{sb} \tag {26}\]3.6 Failure Mode 6 - Epoxy Anchor Bond Failure

This failure mode is only applicable for adhesive anchors.

Because adhesive anchor bond capacity is highly product dependent. You’ll likely need to refer to the manufacturer’s product catalog and ESR report. It may be easier to use their proprietary software for the design of these anchors.

17.6.5.1a - For single adhesive anchor:

\[N_a = N_{ba} \times (\frac{A_{Na}}{A_{Nao}})(\Psi_{ed,Na} \Psi_{cp,Na}) \tag {27}\]17.6.5.1b - For group of adhesive anchors:

\[N_{ag} = N_{ba} \times (\frac{A_{Na}}{A_{Nao}})(\Psi_{ec,Na} \Psi_{ed,Na} \Psi_{cp,Na}) \tag {28}\]Again, this is a lot of variables. Let’s go through them one by one.

17.6.5.2 - Basic Single Anchor Bond Strength (\(N_{ba}\))

The basic bond strength of a single adhesive anchor in tension in cracked concrete is:

\[N_{ba} = \lambda_a \tau_{cr} \pi d_a h_{ef}\tag {29}\]where \(t_{cr}\) is the allowable bond stress provided by the manufacturer. Alternatively, we can use the minimum bond stress value provided in 17.6.5.2.5:

- \(\tau_{cr} = 200 psi\), for outdoor condition cracked

- \(\tau_{cr} = 300 psi\), for indoor condition cracked

- \(\tau_{uncr} = 1000 psi\), for indoor condition uncracked

- \(\tau_{uncr} = 600 psi\), for outdoor condition uncracked

17.6.5.2.5 - If anchor is under sustained tension, multiply \(t_{cr}\) by a factor of 0.4

17.6.5.2.5 - If anchor is under earthquake induced tension, multiply \(t_{cr}\) by a factor of 0.8

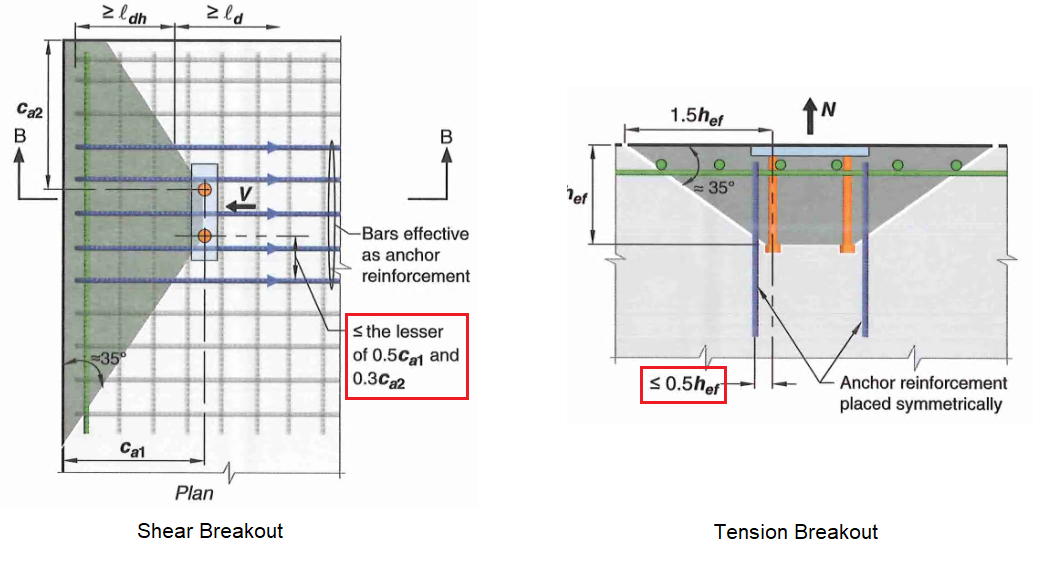

17.6.5.1.2 - Bond Breakout Influence Area (\(A_{Nao}, A_{Na}\))

Figure 6: Concrete Breakout Area For Adhesive Anchors

Figure 6: Concrete Breakout Area For Adhesive Anchors

The breakout influence area is fundamentally different than typical anchors. Rather than \(1.5h_{ef}\), we need to calculate the projected length \(c_{Na}\) which is a function of uncracked bond stress:

\[c_{Na} = 10d_a \sqrt{\frac{\tau_{uncr}}{1100}} \tag {30}\]Then the full breakout area can be calculated as:

\[A_{Nao} = (2c_{Na})^2\tag {31}\]Similarly to before, the projected breakout cone extends a length of \(c_{Na}\) (rather than \(1.5h_{ef}\)) unless interrupted by an edge. Refer to figure 6 for a sample calculation.

17.6.5.3 - Bond Eccentricity Factor (\(\Psi_{ec,Na}\))

Similar to the typical breakout eccentricity factor, just swap \(1.5h_{ef}\) and \(c_{Na}\).

\[\Psi_{ec,Na} = \frac{1}{(1-\frac{e'_N}{C_{Na}})} <= 1.0 \tag {32}\]17.6.5.4 - Bond Edge Effect Factor (\(\Psi_{ed,Na}\))

Similar to the typical breakout edge factor, just swap \(1.5h_{ef}\) and \(c_{Na}\). If the minimum edge distance is at least \(c_{Na}\), then a full breakout cone can form and no edge reduction factor is necessary. Otherwise, if the anchor or anchor group is close to an edge:

\[\Psi_{ed,Na} = 0.7 + 0.3 \frac{ c_{a,min} }{ c_{Na} } \tag {33}\]17.6.5.5 - Bond Splitting Factor (\(\Psi_{cp,Na}\))

Similar to the typical splitting factor, just swap \(1.5h_{ef}\) and \(c_{Na}\). For anchors designed for cracked concrete, the splitting factor can be taken as 1.0. Since we will mostly be assuming cracked concrete, this will be the case.

For anchors designed for uncracked condition:

- \(\Psi_{cp,Na} = 1.0\) if the critical edge spacing \(c_{ac}\) is met, otherwise:

Other Modification Factors

17.5.2.2 - If adhesive anchors are to resist sustained tension, then the capacity must be reduced by 45%.

\[0.55 \phi N_{sa} \tag {35}\]17.10.5.4 - For seismic application, reduce bond capacity by 25%.

\[0.75 \phi N_{sa} \tag {36}\]As you can probably tell already, adhesive anchors are terrible under sustained tension. Reduction factor from 17.5.2.2 and 17.6.5.2.5 stack resulting in a reduction of almost 80%(0.55*0.4=0.22).

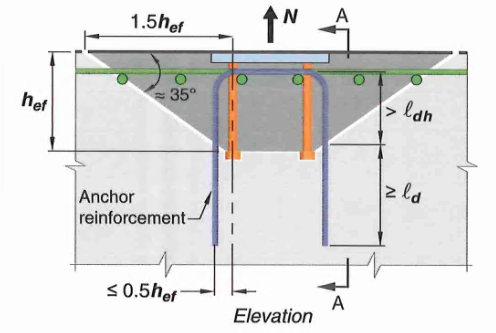

3.7 Failure Mode 7 - Breakout Anchor Reinforcement

Figure 7: Anchor Reinforcement in Blue, Supplementary Reinforcement in Green

Figure 7: Anchor Reinforcement in Blue, Supplementary Reinforcement in Green

17.5.2.1 - Occasionally, it may be impossible to rely on concrete breakout capacity alone. In these cases, we may take breakout capacity as equal to the strength of all anchor reinforcements that can be developed on both ends of the splitting plane.

\[\phi N_{cbg} = \phi f_y A_s \tag {37}\]- fy is the yield strength of anchor reinforcement

- As is the total steel area of anchor reinforcement

- use \(\phi = 0.75\) per 17.5.3,

There are stringent detailing requirements in order to take advantage of anchor reinforcements, here are some of the important ones:

- Reinforcement must be developed on both sides of the breakout line

- For tension breakout, anchor reinf. should be placed as close to the resultant tension as possible. No more than \(0.5h_{ef}\) from anchor centerline

- For shear breakout, anchor should be placed as close to top of slab as possible while basically touching the anchors.

- For shear breakout, anchor reinf. are effective within a width equaling to \(min(0.5c_{a1},0.3c_{a2})\)

- Available research data is based on #5 bars. Larger bend radii of larger bars may reduce effectiveness. Bar larger than #6 not recommended but not prohibited by code either.

Figure 8: Effective Region for Anchor Reinforcement

Figure 8: Effective Region for Anchor Reinforcement

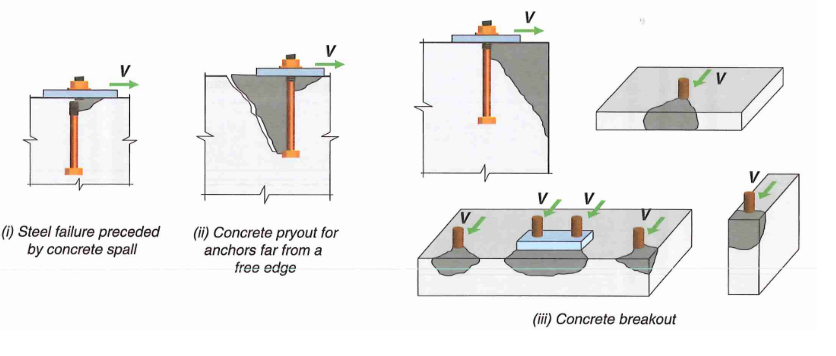

4.0 Shear Strength

Figure 9: Anchor Shear Failure Modes

Figure 9: Anchor Shear Failure Modes

4.1 Failure Mode 1 - Steel Failure

17.7.1.2b - For cast-in headed bolts and anchors:

\[V_{sa} = 0.6* A_{se,N} f_{uta} \tag {38}\]17.7.1.2a - Cast-in headed stud anchors can achieve slightly higher capacity due to fixity provided by the welds between plate and anchor:

\[V_{sa} = A_{se,N} f_{uta} \tag {39}\]17.7.1.2c - For post-installed anchors, look for ESR report from manufacturer

where:

- \(f_{uta}\) = ultimate steel rupture strength (Fu) and shall not exceed 1.9Fy or 125 ksi

- \(A_{se,N}\) = refer to the tensile strength section for how the reduced cross-sectional area can be calculated

Alternatively, follow the AISC 360 provisions and use gross area along with a reduced material strength.

17.7.1.2.1 - For anchors used with built-up grout pad (as is common in base plate connections for leveling), the calculated steel shear strength must be reduced by 0.8.

The above specification is less conservative than the European equivalent ETAG Annex C by a factor of 3 to 10! I will go through this topic in more detail in section 4.4: shear with lever arm.

4.2 Failure Mode 2 - Anchor Pryout

17.7.3 - Concrete pry out strength is simply calculated as a multiple of tension breakout strength

(a) For a single anchor:

\[V_{cp} = k_{cp} N_{cp} \tag {40}\](b) For an anchor group:

\[V_{cpg} = k_{cp} N_{cpg} \tag {41}\]Where:

- \(k_{cp}\) = 1.0 for embedment less than 2.5 inches, or 2.0 for embedment larger than or equal to 2.5 inches

- \(N_{cp},N_{cpg}\) = tension breakout capacity for cast-in/post-installed or adhesive anchors

4.3 Failure Mode 3 - Shear Edge Breakout

Figure 10: Concrete Shear Breakout Failure Cone

Figure 10: Concrete Shear Breakout Failure Cone

17.7.2.1a - For a single anchor:

\[V_{cb} = V_b \times ( \frac{A_{Vc}}{A_{Vco}} ) ( \Psi_{ed,V} \Psi_{c,V} \Psi_{h,N}) \tag {42}\]17.7.2.1b - For an anchor group:

\[V_{cbg} = V_b \times (\frac{A_{Vc}}{A_{Vco}}) (\Psi_{ec,N} \Psi_{ed,N} \Psi_{c,N} \Psi_{h,N}) \tag {43}\]17.7.2.1c - Note that shear breakout may also occur for shear acting parallel to an edge. The breakout capacity in these situations is determined by assuming load acting perpendicular to the edge, then multiply by 2. Edge factor should be taken as 1 in these situations.

\[V_{cb,parallel} = 2 \times V_{cb} \tag {44}\]The equations are essentially the same as tension breakout with a few subscript changes. Let’s go through them one by one.

17.7.2.2 - Basic single anchor shear breakout capacity

17.7.2.2.1 - This is the basic concrete breakout strength, of a single anchor, in cracked concrete. We will use this value as a starting point and apply several modification factors for other conditions. The basic capacity shall be the minimum of:

\[V_{b} = (7 (\frac{l_e}{d_a}) ^{0.2} \sqrt{d_a}) \times \lambda_a \sqrt{f'_c} (c_{a1})^{1.5} \tag {45}\] \[V_{b} = (9) \times \lambda_a \sqrt{f'_c} (c_{a1})^{1.5} \tag {46}\]where:

- \(l_e\) is the bearing length and shall be equal to \(h_{ef}\) for anchor with constant stiffness over the full length and shall not exceed \(8d_a\)

- \(l_e = 2d_a\) for torque controlled expansion anchors with a distance sleeve separated from expansion sleeve

17.7.2.2.2 - The constant “7” in equation (45) may be increased to 8 should the following conditions be satisfied:

- Anchor is continuously welded to a steel attachment plate

- Anchor spacing is at least 2.5 in

- Corner reinforcement provided if \(c_{a2} <= 1.5h_{ef}\)

- attachment plate has thickness greater than \(0.5d_{a}\) or 3/8 in

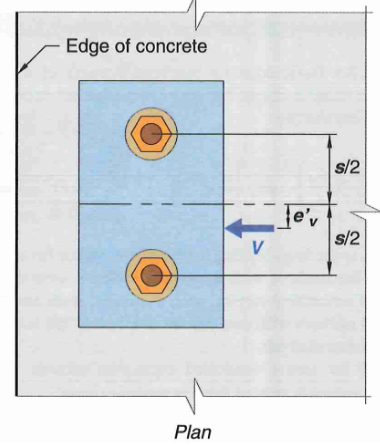

17.7.2.3 - Shear Breakout Eccentricity Factor (\(\Psi_{ec,V}\))

This factor is unique to anchor groups. If the resultant shear on an anchor group is concentric, or if we are looking at a single anchor:

\[\Psi_{ec,V} = 1.0 \tag {47}\]On the other hand, when a moment is applied to an anchor group, the resultant tension is not concentric meaning some anchors are more stressed than others.

\[\Psi_{ec,V} = \frac{1}{1+\frac{e'_V}{1.5c_{a1}}} <=1.0 \tag {48}\]\(e_V\) is the distance from centroid of anchor loaded in shear to the resultant shear force.

Figure 11: Anchor Tension Eccentricity Factors

Figure 11: Anchor Tension Eccentricity Factors

17.7.2.4 - Breakout Edge Effect Factor (\(\Psi_{ed,V}\))

Unlike edge factor for tension, shear breakout is always near an edge. In this case, we have to adjust for the edge parallel to shear force \(c_{a2}\) (if any)

If the \(c_{a2} > 1.5c_{a1}\) then no reduction is necessary.

\[\Psi_{ed,V} = 1.0 \tag {49}\]Otherwise:

\[\Psi_{ed,V} = 0.7 + 0.3 \frac{ c_{a2} }{ 1.5c_{a1} } \tag {50}\]17.7.2.5 - Breakout Cracking Factor (\(\Psi_{c,V}\))

Modification factor for cracking in shear breakout depends on rebar condition near the edge:

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.0\) no supplemental reinforcement parallel to edge (or smaller than #4)

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.2\) reinforcement exists parallel to edge and is #4 or larger

- \(\Psi_{c,N} = 1.4\) reinforcement exists plus sitrrups enclose the supplemental reinf. with spacing not more than 4”

17.7.2.6 - Member Thickness Factor (\(\Psi_{h,V}\))

Breakout capacity in shear is not directly proportional to member thickness (\(h_a\)). This factor accounts for this effect:

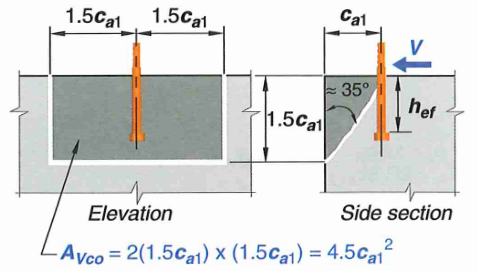

\[\Psi_{h,V} = \sqrt{\frac{1.5c_{a1}}{h_a}} \tag {51}\]17.7.2.1.3 - Full Projected Failure Area of Single Anchor (\(A_{Vco}\))

Based on a 35 degree breakout cone, the projected failure area is a rectangle with side length of \((2)1.5c_{a1}\) and depth of \(1.5c_{a1}\)

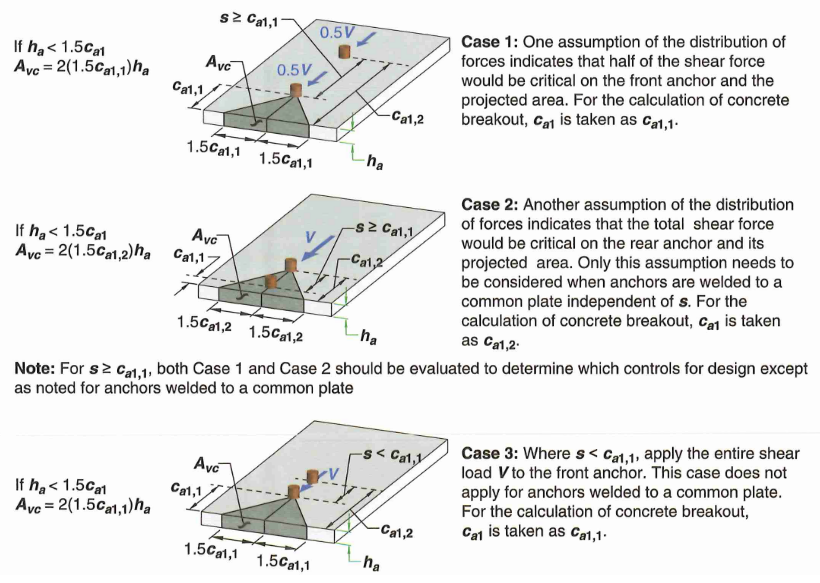

\[A_{Vco} = 4.5c_{a1}^2 \tag {52}\]17.7.2.1.4 - If anchors are located at varying distance welded to an attachment plate. Then the strength can be calculated based on the furthest anchors neglecting other rows of anchors. Refer to the figure below for a better illustration.

Figure 12: Difference Cases to Check For Anchor Groups

Figure 12: Difference Cases to Check For Anchor Groups

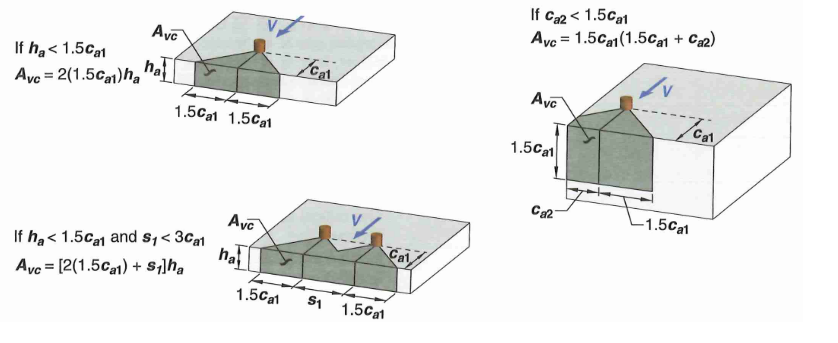

17.7.2.1.1 - Actual Projected Concrete Failure Area (\(A_{Vc}\))

The actual breakout area must be adjusted depending on the perpendicular edge or anchor groups. However, the projected area must not exceed \((n A_{Vco})\) where n is the number of anchor in the anchor group. See figure below for some example calculations.

- Essentially the breakout depth will be equal to \(1.5c_{a1}\) subject to limitation of member thickness

- The width of breakout extends \(1.5c_{a1}\) on either end unless interrupted by an edge

Figure 13: Concrete Breakout Area Example

Figure 13: Concrete Breakout Area Example

17.7.2.1.2 - If the anchor is located in a narrow section where both this member thickness, and \(c_{a2}\) are less than \(1.5c_{a1}\), then \(c_{a1}\) must be adjusted as the maximum of:

- Larger edge distance: \(c_{a2} / 1.5\)

- Member thickness: \(h_a / 1.5\)

- \(s/3\) where s is the maximum spacing perpendicular to direction of shear

4.4 Failure Mode 4 - Shear with Lever Arm (ETAG 001 Annex C)

ACI 318 is silent about shear attachment with lever arm, commonly seen in cladding attachments. For more discussion on this subject, refer to the textbook “Anchorage in Concrete Construction” by Eligehausen, Malle, and Silva (2006). The research findings therein are codified in the European Organization for Technical Approval (ETAG 001 Annex C)

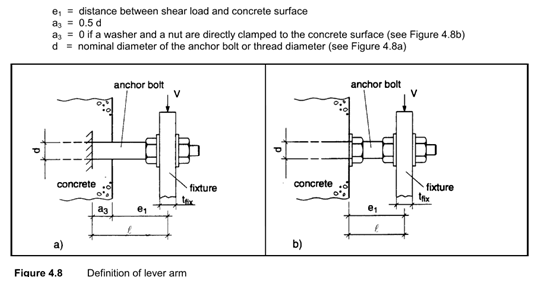

ETAG 001 Annex C 5.2.3.2: Adjusted Shear Capacity With Lever Arm

Rather than imposing additional flexural stress onto the anchors, the additional bending induced by the eccentricity is converted to a reduced shear capacity

\[V_S^M = \alpha_M M_s / L_b \tag {53}\]Where:

- \(M_s\) is the moment capacity of one anchor rod and can be calculated as shown. Note the use of ultimate material strength Fu, as well as reduction based on tension DCR:

- \(L_b\) is the stand off eccentricity as shown below to center of fixture plate. It should be adjusted for a spalling distance of \(0.5d_a\) unless clamped to prevent spalling

Figure 14: Lever Arm Distance

Figure 14: Lever Arm Distance

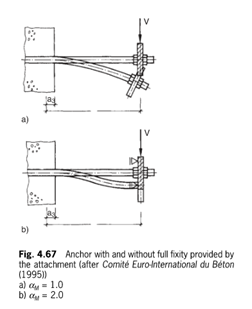

- \(\alpha_M\) adjusts the curvature assumption and ranges from 1 for single curvature bending, to 2 for double curvature bending. The assumption of single curvature bending is appropriate if the fixture can rotate freely which is not the case for base plates. Double curvature can also be achieved by clamping both sides of the plate with nuts and washers

Figure 15: Single and Double Curvature

Figure 15: Single and Double Curvature

ETAG 001 Annex C treatment of Grout Layer

ACI does briefly mention the treatment of shear with grout pads. Per 17.7.1.2.1 the calculated steel shear strength must be reduced by 0.8 (regardless of thickness of grout). However, as we will see shortly, this is less conservative than the European equivalent standards by at least a factor of 3! Most jurisdictions in the US would be content going along with the ACI 318 grout pad 0.8 reduction. However, HCAI or DSA may have more stringent requirements.

The conservatism from the European code primarily comes from the worry that thicker grout pads may spall, leading the front anchors transferring shear primarily via bending. Section 14.4.5.2.2 of the Eligehausen textbook provides the recommendation that lever arm may be neglected only if all the following conditions are satisfied:

- If grout thickness is less than \(d_a/2\)

- If contact length of anchor to base plate is at least \(0.5 t_p\)

- Not using oversized holes

For comparison purposes, a 1.5” diameter, GR 55 anchor rod, with 2” grout layer and 2” plate has the following nominal capacity in each code:

- ACI 318-19: 51 kips

- ETAG 001 Annex C: 16 kips (assuming tension DCR = 0)

If tension DCR is equal to say 40%, then the ACI capacity would remain the same, while the ETAG capacity would be reduced to ~10 kips.

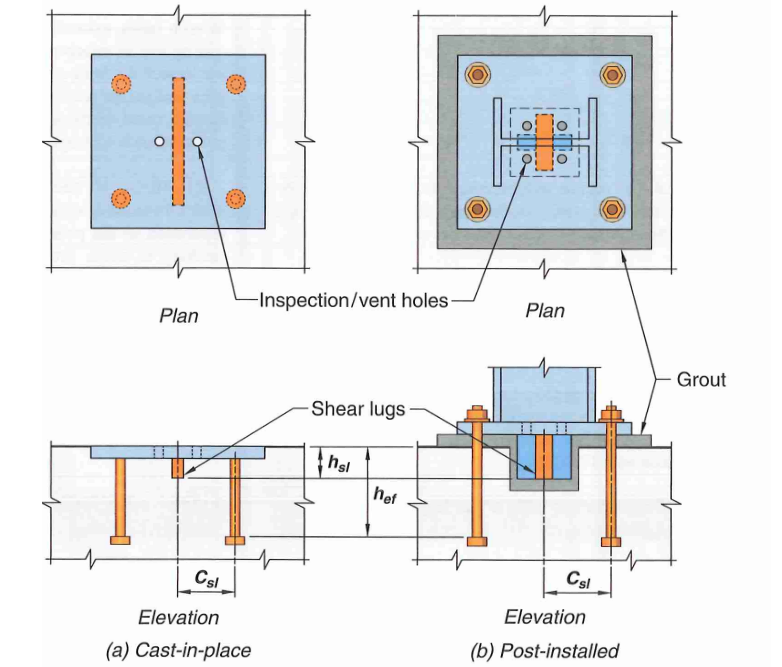

5.0 Shear Lugs

5.1 General

Figure 16: Shear Lugs

Figure 16: Shear Lugs

Shear lugs are rectangular plates, or steel shape composed of plate-like elements welded to a base plate. They resist shear via a bearing mechanism.

17.11.1.1.2 - Minimum of four anchor rods shall be provided when using a shear lug

17.11.1.1.3 - The use of shear lugs enable separation of shear and tension design, provided that the anchors are not welded to the base plate. In other words, the lugs resist shear and the anchor rods resist tension. If anchors are rigidly connected, displacement compatibility implies a certain amount of shear should be resisted by the anchor rods which must be accounted for. The applied shear that each anchor carries is calculated as shown:

- Anchor not welded or rigidly attached to base plate:

- Anchor welded to base plate (\(A_{ef,sl}\) is the bearing area of shear lug:

17.11.1.1.8 - The following dimensional constraints must be satisfied in order to reduce interaction between breakout and anchor in tension.

- anchor embed depth to shear lug depth (\(h_{ef}/h_{sl} >= 2.5\))

- anchor embed depth to distance between shear lug and centerline of anchor in tension (\(h_{ef}/c_{sl} >= 2.5\))

17.11.1.1.9 - Moment due to shear lug shall be added to the overall design moment in the base plate

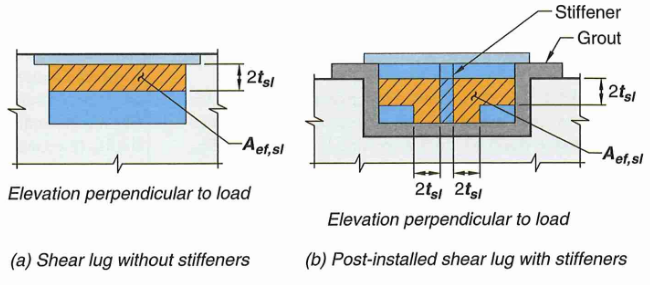

5.2 Bearing Strength

17.11.2.1 - Bearing capacity of shear lug can be calculated as:

\[V_{brg,sl} = 1.7 f'_c A_{ef,sl} \Psi_{brg,sl} \tag {57}\]17.11.2.2 - \(\Psi_{brg,sl}\) is the bearing factor which accounts for effect of axial load:

- No axial load

- Net tension (Pu is -ve)

- Net compression (Pu is +ve)

17.11.2.1.1 - \(A_{ef,sl}\) is the effective bearing area an is concisely illustrated in the figure below

Figure 17: Shear Lug Bearing Area

Figure 17: Shear Lug Bearing Area

5.3 Breakout Capacity

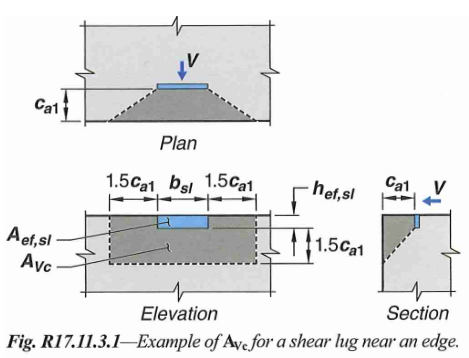

17.11.3.1 - Shear breakout capacity of shear lugs are calculated in the exact same way as section 4.3 of this article. The breakout area is summarized in the figure below

Figure 18: Shear Lug Shear Breakout Area

Figure 18: Shear Lug Shear Breakout Area

Some notes regarding shear lug breakout:

- \(c_{a1}\) is taken as the distance between edge to face of shear lug

- The basic breakout strength is taken as the ceiling value: \(V_{b} = (9) \times \lambda_a \sqrt{f'_c} (c_{a1})^{1.5}\)

- For shear parallel to edge, follow the same recommendation provided in section 4.3 of this article. Use \(c_{a1}\) as distance from edge to center of shear lug. Take eccentricity factor as 1.0

Comments