Right-Hand Rule

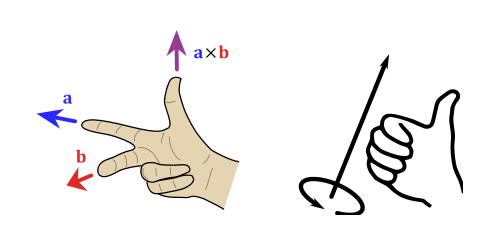

If you’ve ever taken any engineering/physics class in university, then you have undoubtedly been taught the “right-hand rule”. It is apparently a useful mnemonic for remembering cross product conventions and orientation of axes. I can’t really vouch for its usefulness given the fact that I can never quite remember which finger points where.

Recently While developing MSApy, I had to really familiarize myself with the sign conventions of moment/torque vector, as well as ensuring my axes orientations made sense. Everything clicked perhaps out of necessity. There seems to be two versions of the right-hand rule. I call them the “chicken claw”, and the “thumbs up”. I think the “thumbs up” version is undoubtedly superior and easier to remember.

Figure 1: Illustration of Two Versions of Right Hand Rule (source: Wikipedia)

Figure 1: Illustration of Two Versions of Right Hand Rule (source: Wikipedia)

1. General Cross Products

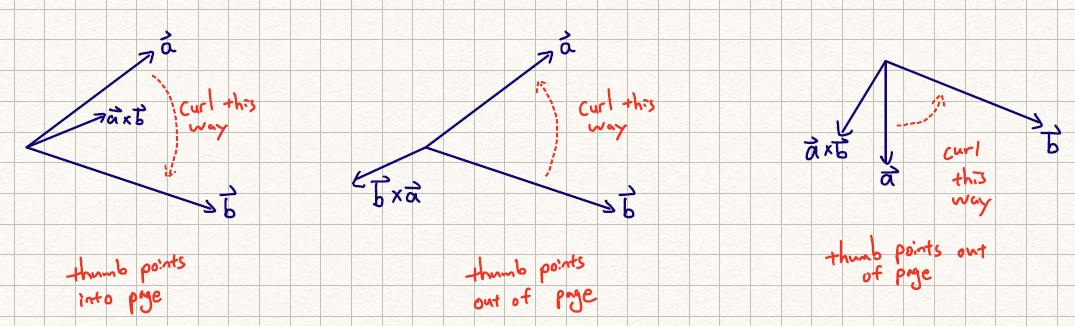

The cross product of two vectors {a} and {b} yield a third vector that is perpendicular to both original vectors. This is pretty much the only thing you need to know about cross-product as a construct. As it turns out, this property has tremendous utility in engineering and physics.

Given two vectors (\(\bar{a}\) and \(\bar{b}\)), what is the orientation of the cross product (\(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}\))?

- With your four fingers, curl from the first vector (\(\bar{a}\)) to the second vector (\(\bar{b}\))

- Your thumb is the orientation of the cross product vector

Figure 2: Examples for Cross Product

Figure 2: Examples for Cross Product

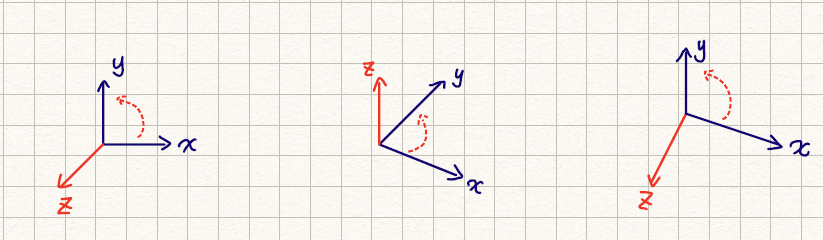

2. Orientation of Cartesian Coordinate

By extension, we can derive the correct right-hand Cartesian coordinate orientation. We know that the unit vectors for a 3-D Cartesian coordinate system are:

\[\hat{i}=\{1,0,0\}, \: \hat{j}=\{0,1,0\}, \: \hat{k}=\{0,0,1\}\]If we perform the cross product of \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\), we can prove that:

\[\hat{k}=\hat{i} \times \hat{j}\]From this, we can derive the correct direction of any third axis when given two others. This is extremely useful when working with local and global axis of line elements. For example,

- Curl from x-axis to y-axis

- Your thumb points towards z-axis

Figure 3: Examples for Cartesian Coordinate Orientation

Figure 3: Examples for Cartesian Coordinate Orientation

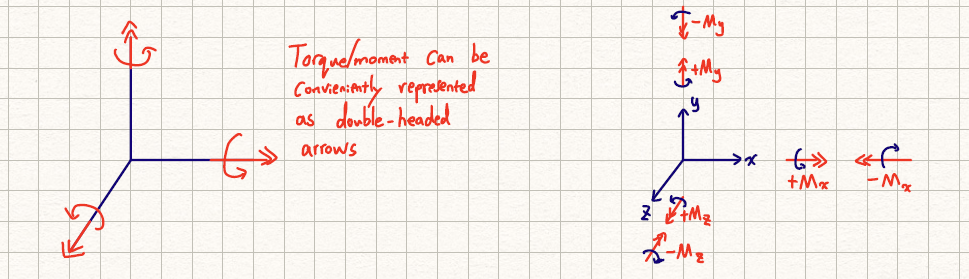

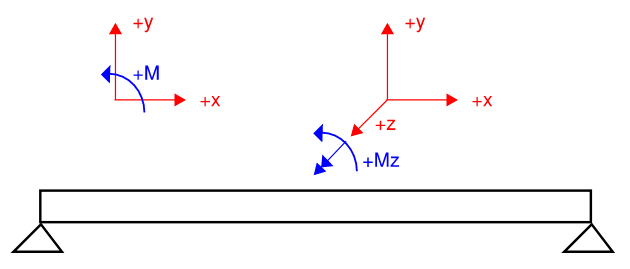

3. Sign Convention of Torque/Rotation

Lastly, right-hand rule can be used to identify direction of moment/torque and rotation. The main trick here is to represent moment as vectors (double-headed arrows) . There are two benefits to doing this:

- Vector addition now applies to moment and it is more intuitive to add one moment to another; rather than “adding” two circular rotation arrows.

- Rather than remembering “counter-clockwise is positive”, or vice versa, which may not even be true and depends on orientation of local vs. global axis, it is much easier to distinguish when a moment is positive vs. negative when they are represented as straight, double-headed arrows. A moment is positive if the double-headed arrow points to the positive axis direction.

Therefore, to determine the sign of a rotation or moment:

- curl your four fingers in the same direction of the rotation/moment

- if your thumb points towards the positive direction of the global axes, then positive. Otherwise negative.

Figure 4: Examples for Using Right-Hand Rule For Torque/Moment Vectors

Figure 4: Examples for Using Right-Hand Rule For Torque/Moment Vectors

Why is Counter-Clockwise Moment Positive?

+x axis points to the right, +y axis points up. By the right-hand rule, +z axis is pointing out of page. As such, if you curl your finger with your thumb pointing towards the +z axis, your fingers curl counter-clockwise.

Figure 5: Why Counter-Clockwise Rotation is Positive

Figure 5: Why Counter-Clockwise Rotation is Positive

Comments