Tea Tasting Journal

As a kid growing up in Toronto, I had fond memories of dim sum on the weekend with my parents. I love dim sum to death! There are no better ways to spend a Saturday morning. One thing I could not understand, however, was my parent’s insistence on ordering Pu’er or chrysanthemum tea to pair with the assortment of culinary masterpieces. It puzzled me. Why would anyone drink this hot leaf water over the objectively superior iced water or Sprite? Back then, if you had asked me what type of tea I enjoyed, you’d be wasting your time. I only knew green, black, and the herbal.

It all started with bubble tea - colloquially known as boba. Of course I had heard of boba before, but I became absolutely obsessed in 2015, and it inflicted great damage on my weight and health. It became especially bad once I started working and had more disposable income. By 2021, I had tried most if not all of the notable bubble tea shops in the Bay Area. I had enough wherewithal to stop eventually. None of my pants fit me anymore, and it’s quite demoralizing to go shopping for new pants. Despite its deleterious effects on my health, bubble tea became a gateway drug for real tea: the ones with better quality, more subtle flavors, and infinitely less sugar.

I had very little interest in tea before my 20s. Now I can’t live without it. This blog documents my journey into the wonderful world of tea.

Tea (茶 - Chá)

“This tea is nothing more than just hot leaf juice!”

“Uncle, that’s what all tea is.”

-Conversation between Uncle Iroh and Prince Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender.

Tea drinking was first recorded in China in 59 BC, possibly earlier. The tea plant - Camellia sinensis - likely originated in Southwestern China in modern day Yunnan, near its borders with Myanmar. Ancient people ate tea before they started drinking it. Most tea drinking occurred for medicinal purposes.

Within China, tea drinking gained prominence during the Tang dynasty when the 8th century writer Lu Yu published a three volume treatise on tea called “The Classic of Tea” (780 CE). The book is divided into ten chapters and served as a seminal text in Chinese tea culture. It covered everything from ideal growing conditions, tools for harvest, best practices for preserving aroma, best utensils, optimal brewing temperature, timing, and ratio, the various tea regions in China, and much more. The fastidiousness reminds me of third-wave coffee culture, except this was during the time of Middle Age Viking raids in Europe.

This amazing beverage simmered quietly in China for another 700 years before the Portuguese traders brought it to Europe in the 1500s. It became quite popular amongst the British Aristocracies, and then later to the broader public. The problem is the price of tea is still quite high. To break up China’s monopoly on tea production, the British successfully introduced tea cultivation in and near India in the 1800s; ending its reliance on China. Assam, Darjeeling, and Ceylon teas are all named after regions in and around India. By the 19th century, large quantities of tea from India and Sri Lanka meant it had become an everyday beverage for all classes of society.

The history of tea is very interesting and worth a read. Tea played a central role in two major historical events that shaped the modern world. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 was a pivotal moment in US history. Whereas the Opium War of 1839 was a pivotal moment in Chinese history. The former was caused by Britain’s export tax on tea shipped to the US. The latter was caused by the lucrative opium trade which was initially introduces as a way to alleviate Britain’s trade deficit with China. The former lead to the creation of a new nation; the latter the decline of an antiquated empire.

The rabbit hole for tea-drinking culture is deep. This is an area of interest that goes back thousands of years. I am not a tea expert. I like tea, but I also like simplicity. Short of ordering test kits on Amazon to measure water hardness and pH levels, here are some general tips that I follow.

Firstly, the ideal brew temperature depends on level of oxidation. Cooler water highlights sweetness but may not fully extract darker teas, while hotter water brings out flavors but can over-extract lighter teas leading to excessive astringency and bitterness. I go for 80° C for green tea, 90° C for Oolong tea, and 100° C for dark tea like Pu’er. Let the tea cool down a bit before drinking. I find that tea actually tastes better once it has cooled down a bit. I almost never cold-brew my tea because I find the taste lacking. The last two points are just personal preference.

Secondly, every tea has an optimal steep time and water-tea ratio. You can easily find specific recommendations online. For one pot steeping, steep time can vary from 2-5 minutes, and ratio can vary from 2-4g of tea per cup (240 mL). Honestly, this probably doesn’t matter. You should find what works for you. Some prefer lighter while others prefer stronger. Some brew one big batch in a teapot, while others prefer multiple infusions with gaiwan.

Last tip: most of us grew up drinking CTC tea, which come in convenient tea bags and steeps very quickly. If it’s your first time drinking loose leaf tea, just remember not to add too much, those tea leaves expand a lot! Some teas are more forgiving than others. For example, Jin Xuan Oolong can be left in the pot for hours as far as I am concerned. On the other hand, loose leaf green tea like Long Jing can get really bitter if you brew too long.

Or just drink tea “Grandpa Style”. Tea is meant to be enjoyed after all. Some like it simple, while others find joy in the fastidiousness and the aesthetic of Gongfu tea.

I will be sampling 14 different tea varieties I bought from Cha Mood. I liked their website design and their tasting set which is why I purchased from them; however, I didn’t know they were located in Europe so I had to pay for international shipping… You can probably find something similar within the US.

Tea Sampler Set From Cha Mood

Tea Sampler Set From Cha Mood

Personal ratings:

| Tea | Rating/5 | Description of Taste |

|---|---|---|

| Moonlight White | ⭐⭐⭐ | Light, elegant floral tea with a hint of sweetness. Strong taste of honey. |

| White Peony (Baimudan) | ||

| Maofeng Green | ⭐⭐⭐ | Grassy, nutty umami with hint of sweet potato. |

| Long Jing Green | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Very similar to Maofeng but maybe lighter. Grassy nutty note and a hint of sweet potato. It’s a beautiful tea visually speaking with its little leafy stubs. |

| Jin Xuan (Milky) Oolong | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | A lighter Oolong. Very smooth, buttery, and silky. No astringency at all. I am not convinced it tastes like milk though. |

| Honey Orchid Oolong | ||

| Alishan Oolong | ||

| Tie Guan Yin Oolong | ||

| Ya Shi Xiang Oolong | ||

| Da Hong Pao Oolong | ||

| Dian Hong Red | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | Light sweetness like Moonlight white but with more complexity. Malty. Hints of dried fruit like raisin or plum. No astringency at all. |

| Lapsang Souchong Black | ⭐⭐⭐ | Tastes very similar to Dian Hong but with a very pronounced smokiness that threw me off (reminded me of bacon or smoked meat). I’m sure I’ll get used to it. |

| Raw Pu’er | ⭐⭐⭐ | Very notable woody fermentation taste. Pu’er by itself is too strong for me. I prefer to mix it with chrysanthemum. |

| Ancient Tree Pu’er | ||

| Dong Ding Oolong | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ | A richer and toastier Oolong taste. Like roasted almond. It has a woody note that kind of reminds me of fresh paper. |

Moonlight White (月光白 - Yuè guāng bái)

Moonlight white tea is produced in the Yunnan province of China. It is picked annually in April. Because it is produced in the same place as Pu’er tea, some people call this tea “white Pu’er”. The leaf buds are crescent shaped like the moon with one side white, and the other dark.

The taste is light, mild, with a floral sweetness that resembles honey. Imagine how honey-water would taste with 1% of its sweetness. This tea is very easy to brew. Astringency and sourness does creep in on longer brews. There is a Chinese phrase that I think perfectly describes Moonlight white: 淡雅花香小甜茶 (light and elegant floral tea with a hint of sweetness).

Mao Feng Green Tea (毛峰 - máo fēng)

Mao Feng green tea is produced near Huangshan (yellow mountain) of Anhui province. The mountain itself is the subject of many traditional Chinese painting and literature. Given its significance in Chinese art and literature, you’ll probably recognize the mountain even if you’ve never been (here are some photos). Between the Tang dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty, apparently more than 20,000 poems were written about Huangshan. Huangshan tea production can be traced back at least a thousand years, beginning in the Song Dynasty and flourishing during the Ming Dynasty.

Maofeng is one of the most well-known green tea variety in China. The Mao Feng varietal apparently was first introduced around 1875 by Xie Yuda Tea House. It made its way to Shanghai and the British merchants praised its taste. 毛峰 (mao feng) can be translated as fur peak, which refers to the tiny white hair on the tea leaves.

The taste is grassy and nutty and reminds me of Long Jing green tea. There is also a noticeable hint of sweet potato. I read online that maofeng is incredibly forgiving and can be brewed forever without becoming astringent and bitter. This was definitely not the case for the ones I bought. I think I would prefer a lighter brew. I will add less leaves next time.

Long Jing Green Tea (毛峰 - máo fēng)

Long Jing tea - sometimes translated literally as Dragon Well green tea - is a variety of pan-roasted green tea produced in Hangzhou, China. Long Jing tea is arguably the most famous tea in China and has a lot of cultural significance. The nearby West Lake is world-renowned for its natural beauty and historical/cultural relics. The lake has influenced Chinese poets and painters for centuries, and has supposedly shaped the aesthetics of garden design in China, Japan, and Korea.

West Lake is one of the most visited tourist destinations in China. In fact, the lake has been a famous tourist destination since at least the Tang dynasty (618-907). To give you a sense of scale: during a seven-day period in October 2024, the lake received 4.4 million visitors. I was there in 2018, and I can confirm both the Lake’s beauty, and the abundance of tourists which I am sadly a part of.

According to legends, while on a vacation in Hangzhou, the Qianlong Emperor visited West Lake and was served some Long Jing tea. He was so impressed that he conferred the 18 tea brushes that produced the tea special imperial status.

The name “Longjing” supposedly originates from a famous well that contained relatively dense water. After heavy rain, water from the well mixes with fresh rainwater and various sediments to produce surface patterns that resembled the movement of a Chinese dragon (Long). Furthermore, the tea is apparently best served with water from Hupao spring - a famous site near West Lake.

The taste of Long Jing is very similar to Maofeng but perhaps a couple of degrees lighter. I noticed a grassy or nutty note and a hint of sweet potato or chestnut. Long Jing tea is immediately recognizable with its little leafy stubs and green hue. It’s a beautiful tea both in taste and in appearance.

Jin Xuan (Milky) Oolong Tea (金萱 - jīn xuān)

Unlike the more traditional oolongs like Tie Guan Yin or Da Hong Pao, Jin Xuan is a relatively new cultivar of oolong tea produced in Taiwan. It was cultivated by the Taiwan Research and Extension Station of Taiwan (TRES) in the 1980s through careful selective breeding. Jin Xuan was named after the grandmother of its creator, Wu Zhenduo, who many consider to be the father of Taiwanese tea. His goal was to create a tea plant that was resistant to diseases, high-yielding, and flavorful. Nowadays, Jin Xuan the third most popular cultivar in Taiwan is grown all over Taiwan, particularly in regions such as Nantou, Chiayi, and Miaoli. This variety of oolong is known for its naturally creamy, buttery taste, which is why it’s also known as “Milky oolong”.

I think this variety of oolong is quite light compared to the other ones I’ve tasted. It’s smooth, buttery, and silky. No astringency at all. Although it is quite smooth, I am not convinced it tastes like milk, and I prefer oolong with a darker note.

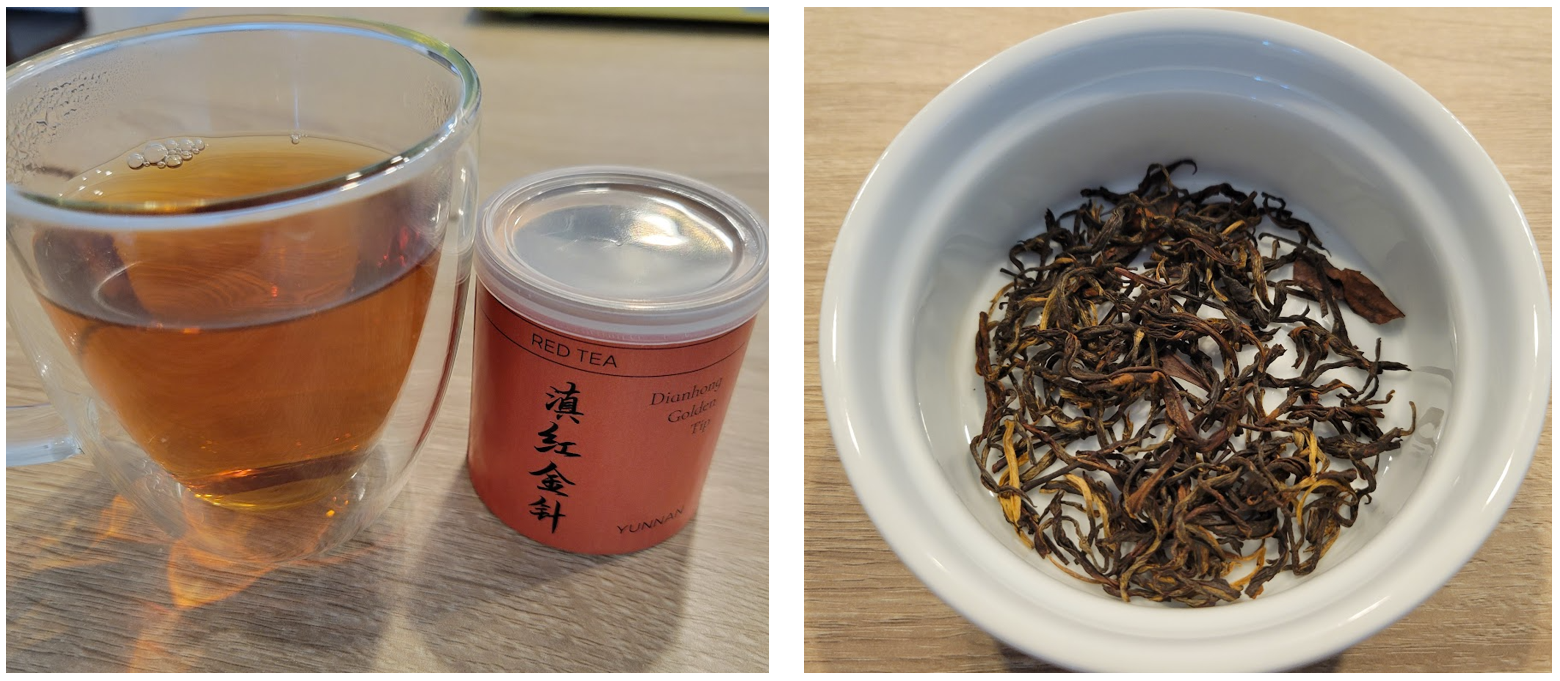

Dian Hong Red Tea (滇紅 - Diān hóng)

Dian Hong red tea is a relatively new cultivar created in the 1930s in the mountainous canyon area west of the Lancang River and east of the Nujiang River in southwestern Yunnan. It enjoys a gourmet, high-end reputation in former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and London. The word 滇 (dian) is a short name for Yunnan, whereas the word 紅 (hong) means red. As such, Dian Hong is often referred to as Yunnan red, or Yunnan black tea. As a sidenote, Western audiences usually categorize tea as either green or black. In China, there are actually three tea categories in common parlance: green, red, and black. Black is used exclusively to describe fermented tea such as Pu’er.

Visually speaking, the tea leaves are a mix of dark and striking golden tips. After brewing, the liquid turns into a deep reddish orange that is incredibly appealing. It smells sweeter than it tastes. The taste is similar to Moonlight white. There is a hint of floral sweetness. But unlike the moonlight white tea, there is a malty note that reminds me of dried fruit like raisin or plum.

Lapsang Souchong Red Tea (正山小種 - zhèngshān xiǎozhǒng)

Lapsang Souchong is the first black tea and the ancestor of all black teas consumed outside of China (e.g. Lipton). It was first brought to Europe in the 1600s and became incredibly popular within the British Royal family. They loved drinking it in the afternoon along with an assortment of snacks, setting the trend for what we now call afternoon tea. In some ways, lapsang souchong is the OG varietal that kickstarted the global tea trade, and the large scale commercial production of tea in China.

Authentic lapsang Souchong is grown in the Wuyi Mountains of Fujian, in a village called Tong Mu. The village is culturally and historically significant and is situated within the Wuyi Mountain Nature Reserve. Lapsang Souchong is the Fuzhou dialect of 正山小種 (zhengshang xiaozhong), which literally translates to “authentic mountain small varietal”. During the height of the global tea trade with Europe, teas grown in Wuyi were seen as high-quality (rightfully so) and fetched a high price. “Zhengshang” was added to distinguish the “real stuff” from the counterfeit tea grown outside of Wuyi. “xiaozhong” simply refers to the size of the tea leaves. There are three categories of red tea: small varietal (Lapsang), gongfu red (e.g. Dian Hong), and CTC (cut, tear, curl) powder-like tea such as Lipton.

The story of how this tea was invented - which may be apocryphal - involved soldiers traveling through the region during the Taiping Rebellion. The soldiers used the sacks of tea leaves as mattresses to sleep better. Their presence significantly delayed tea production. Rather than throwing all the tea leaves away and eating the loss, local farmers put them over pine wood smoke to speed up the drying process. Unfortunately, the locals were more accustomed to drinking lighter loose leaf teas, and so the smoked tea had to be taken to a faraway port market and sold at a low price. To the producer’s surprise, the merchants came back next year demanding more.

The bold smoky flavor of lapsang souchong makes it a love-it-or-hate-it tea. Many believe the smoking processes is used as a means of creating marketable product from older less flavorful tea, and thus avoid it. However, the production of authentic, smoked lapsang souchong is actually highly intricate. Its bold smoky flavor comes from a special smoking process which occurs in a 3-story smokehouse called a Qing Lou (black house). The drying, withering, and smoking process all require decades of experience from tea masters.

In 1848, Scottish botanist Robert Fortune disguised himself as a Chinese merchant (with Qing bald ponytail que hairstyle) in order to travel to Tong Mu village. He had to go to such length because foreigners were historically not allowed outside of treaty ports in Canton or Shanghai. In Tong Mu, he began studying black tea production and succeeded in acquiring seeds of nearby tea trees. His effort eventually allowed the British East India Company to break up the Chinese monopoly on tea production with teas produced in India.

I’m quite fond of the taste. It’s very similar to Dian Hong with its malty raisin sweetness. The dried tea leaves feel brittle and look almost burnt; however, I don’t think it’s particularly strong or bitter. What really threw me off was the smoky aroma. It reminds me of bacon and smoked meat. I don’t think you taste the smoke, but it’s very pronounced and lingers in your nose. I also get a weird coarseness in my throat after drinking it. I’m sure it will grow on me. Apparently lapsang is also used as a spice in soup, stews, and stocks. It also apparently pairs well with single malt whisky, no wonder Winston Churchill was so fond of it.

Dong Ding Oolong Tea (凍頂 - Dòng Dǐng)

(This one is from my pantry and not part of the Cha Mood tasting set.)

Dong Ding oolong tea is produced in Taiwan and named after the mountain where it is cultivated, near Lugu Township, Nantou. Because of its popularity and demand, Dong Ding oolong is now grown all over Taiwan. The original Dong Ding plants were brought to Taiwan from the Wuyi Mountains in China’s Fujian Province 150 years ago. Since then, it has been refined through annual competitions. The Lugu farmer’s association, and the Dong Ding Tea Cooperative are both bodies that run annual competitions for this variety. Compared to other high-mountain oolong teas from Taiwan, the Dong Ding mountain is only around 600 to 900 m (compared to Alishan at 1300m and Lishan at 2000m). Dong Ding translates to “icy peak” or “frozen summit”.

I think I’m most familiar with Dong Ding oolong which might explain my fondness for it. The taste is rich and toasty, like roasted almond. It’s stronger than lighter varieties like Jin Xuan. It has a woody note that kind of reminds me of fresh envelope paper.

WORK IN PROGRESS…

…

Sources of information:

Before my tea-tasting sessions, I usually spend an hour or two reading more about the tea I’m tasting that day. I start by reading the relevant articles on Wikipedia and Baidu 百科. The Baidu wiki entries tend to be more insightful and the information have greater depth. Then, I read various tea blogs, Reddit discussions, and perhaps watch a few videos. I find it helpful for me to read how others describe a tea’s aroma and taste. I don’t have a particularly refined palate. Sometimes I recognize a particular note, but I don’t have the requisite vocabulary to describe it. Through my reading sessions, I’ve come across some tea blogs that are just incredible! They read better, have more personality, and very often have more depth than the wiki articles. However, it’s tough to distinguish the ones trying to sell you tea (with incredibly shallow information), and the ones written by tea connoisseurs/lovers. Here are some that I really enjoyed. Please let me know if there are others I should check out.