Book Journal: String Theory

Roger Federer

Roger Federer is the greatest tennis players of all time.

Nadal may have a better record on clay, Djokovic may have a better record everywhere, but neither can, nor has anyone ever matched the grace and elegance of Federer’s tennis.

I get emotional watching these. I think human beings naturally reach out to truth and beauty, and in Federer I’ve tasted the absolute pinnacle of perfection. David Foster Wallace described this feeling best:

[Top athletes] are beautiful. Jordan hanging in midair like Chagall bridge, Sampras laying down a touch volley at an angle that defies Euclid. And they’re inspiring. There is about world-class athletes carving out exemptions from physical laws a transcendent beauty that makes manifest God in man. […] Great athletes are profundity in motion. They enable abstractions like power and grace and control to become not only incarnate but televisable. To be a top athlete, performing, is to be that exquisite hybrid of animal and angel that we average unbeautiful watchers have such a hard time seeing in ourselves.

David Foster Wallace

Apologies for the excessive Federer rambling. Two sentences turned into multiple paragraphs and 6 hours of YouTube highlights. You may be wondering why I am talking about Federer in a book journal on David Foster Wallace (DFW). Well, If there’s one thing I enjoy more than watching Federer play tennis, it is reading DFW’s writing about Federer playing tennis. His New York Times article Roger Federer As Religious Experience is still my all-time favorite piece of sports journalism. The quality of the article convinced me to pick up String Theory - the subject of this book journal. I’m starting with a slimmer DFW book. Maybe one day I’ll have the courage to read Infinite Jest.

I find DFW quite Federer-esque as a writer. What I mean is that both are masters of their craft. There is a certain “looseness” that I’ve come to recognize in experts. As a mediocre writer, reading DFW makes me feel like I am mentally constipated. Some nights, I manage to squeeze out - with significant exertion - two mediocre paragraphs, only to delete them the next morning. Discovering DFW is like going ice skating for the first time, spending an entire hour trying to stand up, meanwhile, a guy is skating backwards, jumping around, and doing triple axels.

DFW’s style of writing is quite distinctive. You’ll know it when you see it. It can be characterized by incisive commentaries, highly intricate and descriptive sentences, and an astonishing level of intellectual depth suffused with wit and ironic humor. Beneath it all lies a dash existentialism that’s sometimes dark but always empathetic. To give you a taste, here’s a footnote about the hassle of going to the concessions during a professional tennis match:

You can leave your seat only during the ninety-second break between odd games, then you have to sort of slalom a long and Hobbesian line, hand over a gouge-scale sum, and then schlep back up the ramp, bobbing and weaving to keep people’s elbows from knocking your dearly bought concessions out of your hands and adding them to the crunchy organic substratum of spilled concessions you’re walking on… and of course by the time you find the ramp back to your section of seats the original ninety-second break in the action is long over - as, usually, is the next one after that, so you’ve now missed at least two games - and play is again under way, and the ushers at the fat chains prevent re-entry, and you have to stand there in an unventilated cement corridor with a sticky and acclivated floor, mashed in with a whole lot of other people who also left to get concessions and are now waiting until the next break to get back to their seats, all of you huddled there with your ice melting and kraut congealing and trying to stand on tip-toe and peer ahead to the tiny chained arch of light at the end of the tunnel and maybe catch a green glimpse of ball or some surreal fragment of Philippoussis’s left thigh as he thunders in toward the net or something… New Yorker’s patience w/r/t crowds and lines and gouging and waiting is extraordinarily impressive if you’re not used to it; they can all stand quiescent in airless venues for extended periods, their eyes’ expressions that unique NYC combination of Zen meditation and clinical depression, clearly unhappy but never complaining.

“Slalom a Hobbesian line”, “crunchy organic substratum of spilled concessions”, “NYC combination of Zen meditation and clinical depression”. How does he come up with this stuff? My markdown editor keeps trying to change “acclivated” to “acclimated”… DFW’s vocabulary was evidently prodigious, as was his writing ability. Despite the long sentences, there’s a certain flow and rhyme that makes reading DFW downright hypnotic. The overly granular descriptions teleports you to the scene, and the witty digressions make it feel like you are exploring all the neurotic recesses of his mind. All of this for a throwaway footnote.

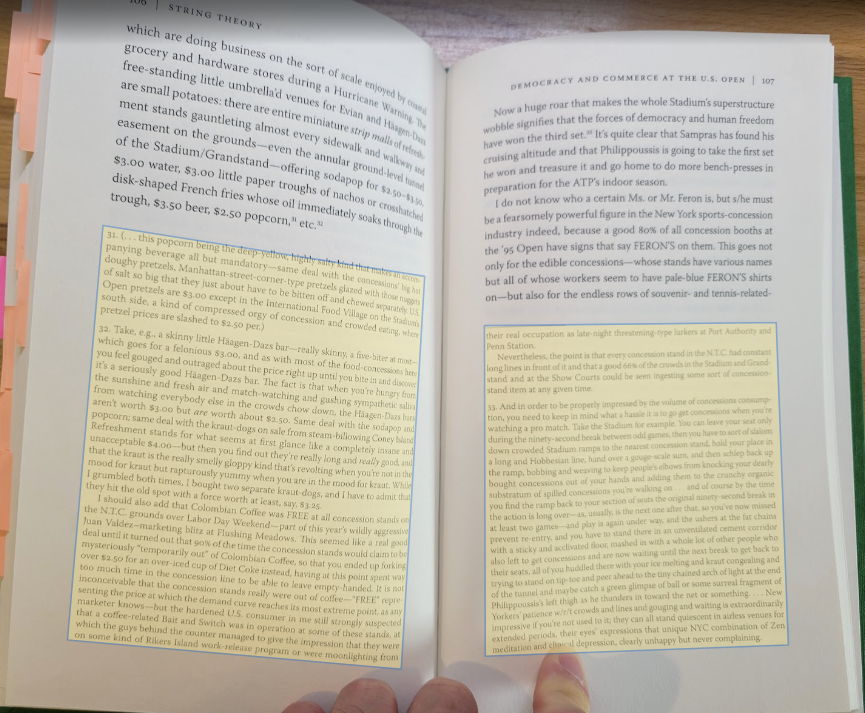

Speaking of footnotes, the essays in String Theory (and his writing in general) are choke full of them. It’s normal to have footnotes, but the sheer abundance of it is something to behold. I’m glad the editor decided to keep the footnote within the bottom margins rather than at the end of the book. I think reading the offbeat and lengthy digressions is an essential part of the DFW experience. I mean just look at this page. Footnotes are highlighted in yellow.

Footnotes in DFW’s Writing

Footnotes in DFW’s Writing

String Theory

String theory is a short book consisting of five essays related to the game of tennis, which DFW played competitively as a junior. It was an incredibly fun read. I haven’t read 140 pages in one sitting in a very long time.

–

The first essay is a memoir about his experience growing up in the rural parts of Illinois. He recounts his early years as a bookish, physically awkward teenager who’s good at math and tennis. He reflects on his experience as a high ranked junior player, tells tales of friendship and rivalry, and shares his inner thoughts on the game of tennis. There were humorous descriptions of the absurdly strong winds in the flatlands in Illinois. There were explorations of the insecurity of his youth and that of the Midwest. It’s hard to encapsulate it all into a single paragraph. I doubt there was a central message to tie it all together. It’s all one big stream of consciousness that’s highly introspective and filled with interesting digressions.

–

The second essay is a book review of Tracy Austin’s memoir. Calling her book dull and vapid would have been too easy. Instead, DFW turns this book review into an existential exploration of the psyche of top athletes, the apparent vapidness of their lives beyond sports, and the disappointing flatness of all sport biographies.

There’s not even a recognizable human being in here. And this isn’t just because of clunky prose or luxated structure. The book is inanimate because it communicates no real feeling and so gives us no sense of a conscious person. There’s no body at the other end of the line. Every emotionally significant moment or event or development gets conveyed in either computeresque staccato or else a prepackaged PR-speak whose whole function is to deaden feeling. […] listen again to her report of how winning her first U.S. Open felt: “I immediately knew what I had done, which was win the U.S. Open, and I was thrilled.” This line haunts me; it’s like the whole letdown of the book boiled down into one dead bite.

Reading DFW’s scathing critique is enjoyable in the same way watching the NBA slam dunk contest is enjoyable; however, don’t be mistaken by the harsh words. DFW was a huge fan of Tracy Austin. She was a teenage tennis prodigy who won the U.S. Open at 16 years of age. Back when DFW was a junior player, Tracy Austin must’ve seemed invincible. Yet such a sub-par memoir wasn’t just disappointing to DFW, it was depressing, even heartbreaking (I’ve read plenty of bad books, but none were bad enough to give me melancholy).

He makes the observation is that most people, him included, falsely assume people who are geniuses as athletes are also geniuses as speakers, and that they are articulate, perceptive, profound even. But way too often, they turn out to be a veneer of outer perfection wrapped around a vapid interior. It would seem that most gifted athletes are incapable of explaining the qualities and experiences that constitute their fascination, which means disappointing sports autobiographies for the rest of us. (Agassi’s memoir - Open - is an obvious counterexample to the pattern DFW described here. It was incredibly well-written and became a national bestseller in 2009)

[…] It may well be that we spectators, who are not divinely gifted as athletes, are the only ones able truly to see, articulate, and animate the experience of the gift we are denied. And that those who receive and act out the gift of athletic genius must, perforce, be blind and dumb about it - and not because blindness and dumbness are the price of the gift, but because they are its essence.

–

The third essay is a profile of Michael Joyce, a promising young American ranked 79th in the world at the time. The actual name of the essay is: Tennis Player Michael Joyce’s Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Limitation, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness - which tells you a lot about DFW and the disparate topics covered therein. DFW immersed himself in Joyce’s daily routine at the 1995 Canadian Open in Quebec. Through DFW’s eyes, we get a behind-the-scenes look at the physical and mental demands of a professional tennis player. He explores many disparate topics such as the little intricacies of tennis, stylistic differences of players, how much water the pros drink, and too many digressions to list. The most important topic, and the one DFW concludes with, is the requisite commitments and sacrifices the pros must make. Greatness demands sacrifice, and while it is true we celebrate great athletes, we tend not to think about the almost-greats and the tragedy of their singular focus. Here it is verbatim:

But we prefer not to countenance the kinds of sacrifices the professional-grade athlete has made to get so good at one particular thing. Oh, we’ll play lip service to these sacrifices - we’ll invoke lush cliches about the lonely heroism of Olympic athletes, the pain and analgesia of football, the early rising and hours of practice and restricted diets, the privations, the prefight celibacy, etc. But the actual facts of the sacrifices repel us when we see them: basketball geniuses who cannot read, sprinters who dope themselves, defensive tackles who shoot up bovine hormones until they collapse or explode. We prefer not to consider the shockingly vapid and primitive comments uttered by athletes in post-contest interviews, or to imagine what impoverishments in one’s mental life would allow people actually to think in the simplistic way great athletes seem to think. Note the way “up-close and personal profiles” of professional athletes strain so hard to find evidence of a rounded human life - outside interests, activities, charities, values beyond the sport. We ignore what’s obvious. that most of this straining is farce. It’s farce because the realities of top-level athletics today require an early and total commitment to one pursuit. An almost ascetic focus. A subsumption of almost all other features of human life to their one chosen talent and pursuit. A consent to live in a world that, like a child’s world, is very serious and very small.

[…] Michael Joyce is, in other words, a complete man (though in a grotesquely limited way). But he wants more. Not more completeness; he doesn’t think in terms of virtues or transcendence. He wants to be the best, to have his name known, to hold professional trophies over his head as he patiently turns in all four directions for the media. He is an American and he wants to win. He wants this, and he will pay to have it - will pay just to pursue it, let it define him - and will pay with the regretless cheer of a man for whom issues of choice became irrelevant long ago. Already, for Joyce, at twenty-two, it’s too late for anything else: he’s invested too much, is in too deep. I think he’s both lucky and un-. He will say he is happy and mean it. Wish him well.

–

The fourth essay is about his experience at 1996 U.S. Open. He talks about the hyper-commercialization of the tournament. Sponsorships, $30 dollar t-shirts (in 1996!), gouge-scale prices at the concession stands, corporate ticket sales, MASTERCARD, VISA, CHASE, USTA, EVIAN, HAAGEN DAZS. It was thoroughly enjoyable and filled with witticisms, irony, and humor. DFW can be moody and dark, but it’s also evident that he can be quite a comedian if he wants to. He has this extraordinary ability of turning the mundane into something amusing. He can write a book about paint drying and I’m sure it’d be a page-turner.

–

The fifth and final essay is about Roger Federer, it’s a printed copy of that famous New York Times article Roger Federer As Religious Experience that I referred to earlier in this post. I will not try to summarize this here. Go read it yourself. It’s incredibly good.

I started this book journal with 6 hours of Federer YouTube highlights, and I intend to end with one. Thanks for reading!