Reading Journal: How to Win Friends and Influence People

“The ability to speak is a shortcut to distinction. It puts a person in the limelight, raises one head and shoulders above the crowd. And the person who can speak acceptably is usually given credit for an ability out of all proportion to what he or she really possess”

– Lowell Thomas

What a pleasure it was to read this book again. I was first introduced to this classic through audible. As the magnum opus of all self-help books, I felt it necessary for me to read it thoroughly and make notes. I found the message and principles to be helpful in both my personal life and my professional career, and thus I decided to purchase a physical copy as well.

Supposedly, Warren Buffet only has one certificate on his office wall. It’s from the course he took from Dale Carnegie. It is hard to overstate just how influential and great this book is.

Here is a brief summary of the important messages within each part, and quotes that I thought were thought-provoking.

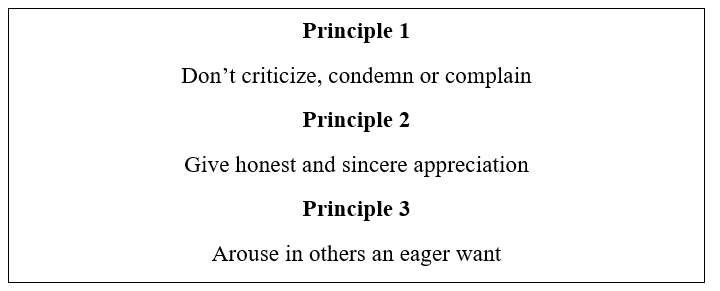

- Part 1 - Techniques in Handling People

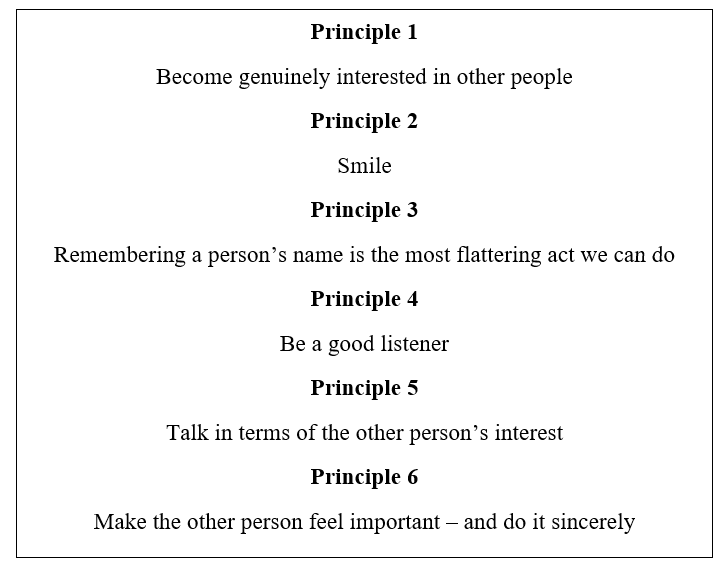

- Part 2 - Ways to Make People Like You

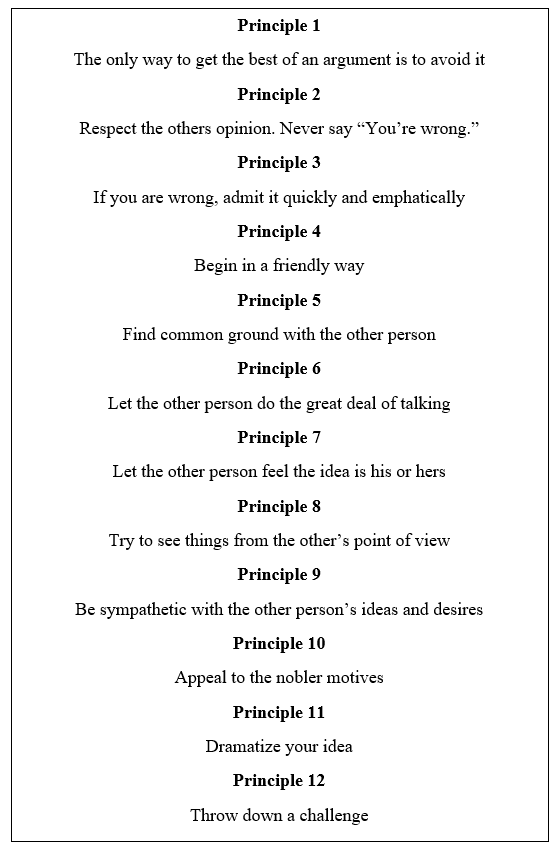

- Part 3 - How to Win People to Your Way of Thinking

- Part 4 - How to Be a Leader

Part 1 - Techniques in Handling People

The first principle is to not criticize, condemn, or complain. The author begins the chapter by introducing two of the most hated, and despicable criminals in American history. Despite their criminal activities, neither see themselves as wrong-doers.

“There you are; human nature in action, wrongdoers, blaming everybody but themselves.”

Carnegie argued that criticisms are largely ineffective. Most people will just justify himself or herself and condemn you back. Even for an educated mind, admitting wrong-doing is not very pleasant. As Abraham Lincoln once said:

“Judge not that ye be not judged.”

And when others spoke harshly of the southern people, Lincoln replied:

“Don’t criticize, they are just what we would be under similar circumstance.”

So the next time we become disgruntled and want ways to express our frustration through criticism, realize that it won’t do any good in the long run. Yes, it will relieve our negative feelings, but it will just make the person justify himself. It will make him condemn us and arouse unnecessary hard feelings. For sharp criticisms and rebukes almost invariably end in futility, it is much better to try to understand, as it breeds sympathy, tolerance, rather than contempt.

“Let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic. We are dealing with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudices and motivated by pride and vanity.”

“Any fool can criticize, condemn and complain – and most fools do. But it takes character and self-control to be understanding and forgiving”

God himself does not propose to judge man until he end of his days, so why should you and I?

The second principle is to give honest and sincere appreciation. The chapter begins by stating that the only way you will get anyone to do anything is if they want to do it. Resorting to tyrannical forces is out of the question and will have undesirable repercussions. So how do you make others WANT to do something?

As Sigmund Freud once said that all motivation stem from two sources: The sex urge and the desire to be great. John Dewey puts it in another way: “The desire to be important.” This is perhaps the most important lesson in this book, and it is one that will be repeated over and over.

Despite the fact that all humans crave the feeling of importance, the hunger is rarely satisfied. Yet it is this desire that make us wear the latest style, drive the best cars, and talk about all our achievements. If this desire to feel important is the root motivation, why don’t we take advantage of it in our daily interactions with other people. We do so by being

“hearty in our approbation, and lavish in our praises.”

People work better after approval rather than condemnation. We must not fall into the habit of saying nothing when everything goes right, then bawl out at our subordinates when things go wrong. A little praise can go a long way. Your words of appreciation may stay with others, and they will treasure them and repeat them years after you have forgotten them.

One important caveat is to know the difference between appreciation and flattery. One comes from the heart, while other from the teeth. One is unselfish while the other is selfish. One is admired while the other is condemned. When we show appreciation for others, it is of the utmost importance to be sincere.

The third principle is to arouse in others an eager want. When trying to pursue others to do what you want. It is extremely helpful to reword your request in a way that aligns with the interest of the other person. In short, they next time you wan to persuade somebody to do something. Ask yourself: “How can I make this person want to do it?”

“Why talk about what we want? That is childish. Absurd. Of course, you are interested in what you want. You are eternally interested in it. But no one else is. The rest of us are just like you: We are interested in what we want.”

“The only way on earth to influence other people is to talk about what they want and show them how to get it.”

The chapter proceeds to talk about the importance of seeing things from the others prospective. Several examples of business letters and emails were provided to show how the above tip can be used to elicit a more favorable response. For instance, see the two emails below and compare their tone and effectiveness. One focuses on me while the other focuses on the other person.

-

“Our freight train are congested in the afternoons on Wednesday, and we require you to move your shipments to the morning hours to ease congestion.”

-

Say instead: “We are grateful for your patronage over the years and we are eager to give you speedy and efficient service. However, our commitment will not be possible this upcoming Wednesday due to the influx of customers, congestion will arise and your trucks will unavoidably be held up and delayed. That is terrible and can be avoided. If you make your deliveries in the morning when possible, your freight will get our immediate attention. Regardless of when your shipments arrive, we will always do all in our power to serve you promptly”

Part 2 - Ways to Make People Like You

The first principle is to become genuinely interested in other people. The chapter starts with a fun and enlightening anecdote. If we want to be liked by other people, why not learn from the best winner of friends the world has ever known? A dog is loved because he is always happy. There are no ulterior motives behind his happiness. He’s not trying to sell you real estate or trying to marry you. A dog is the only animal in the world that doesn’t have to work a single day in his life. A dog makes his living by giving you nothing but love.

Therefore, if you want to make more friends, become genuinely interested in other people. It is ineffectual to put in the effort to get others interested in you. Instead, look for things that interest the other person, and become sincerely interested in him/her. It is human nature for us to enjoy the presence of people who are interested in us.

“We are interested in others when they are interested in us.” – Publilius Syrus

One suggestion that the author made was to make a habit of remembering another person’s birthday.

The second principle is to smile. Such a simple rule, yet this rule will probably have the most profound impact on your life. The positive response from showing a genuine smile is well worth the little amount of effort that is needed. The author also mentioned that smiling while talking with someone over the phone may be helpful. And that the smile often comes through your voice.

However, heed this warning! A genuine smile is not the same as an insincere grin. A grin like that does not fool anyone. If you want to smile. Force yourself to be genuine. It all comes down to a mental attitude; and changing it is a simple matter.

“Most folks are about as happy as they make up their minds to be” – Abe Lincoln

So the next time you go out the door, keep your head held up high and drink in the sunshine. Greet others with your smile. Do not fear being misunderstood and do not waste a minute thinking about your enemies. The impact of a smile is beautifully articulated below in “The Value of a Smile at Christmas”

It costs nothing, but creates much.

It enriches those who receive, without impoverishing those who give.

It happens in a flash and the memory of it sometimes lasts forever.

None are so rich they can get a long without it, and none are so poor but are richer for its benefits.

It creates happiness in the home, fosters good will in a business, and is the countersign of friends.

It is rest to the weary, daylight to the discouraged, sunshine to the sad, and Nature’s best antidote for trouble.

Yet it cannot be bought, begged, borrowed, or stolen, for it is something that is no earthly good to anybody till it is given away.

And if in the last-minute rush of Christmas buying some of our salespeople should be too tired to give you a smile, may we ask you to leave one of yours?

For nobody needs a smile so much as those who have none left to give!

The third principle is to remember other’s name. It seems a frivolous task to remember the name of every person we meet, but it can have significant impact on our social lives. The chapter begin with anecdotes about how remembering people’s name benefitted many successful people including Franklin Roosevelt.

Remembering another person’s name is the quickest way to make other people like you. Most people don’t remember names because they think the time and energy necessary to concentrate and repeat and fix names in their mind is not worth the effort. They come up with excuses like they are too busy. Therefore, remembering someone else’s name says to that person: “You matter to me, so I have taken the effort to remember your name.”

The next time you meet new people, spent extra effort in remembering their names. As soon as they introduce themselves, repeat the name in your head 10 times and associate their face with that name. It is well worth the effort!

The fourth principle is to be a good listener. In far too many cases, people are too concerned with what they are going to say next rather than keeping their ears open. The power of a good listener cannot be underestimated. Even the most violent critic will soften and subdue in the presence of a patient and sympathetic listener. As Jack Woodford wrote:

“Few human beings are proof against the implied flattery of rapt attention”

The next time you interact with someone, don’t focus too much on keeping the conversation flowing. Instead, listen attentively; give the talker your undivided attention.

The fifth principle is to talk in terms of other’s interest. This is a short chapter. It begins with an anecdote of how Teddy Roosevelt stay up late the night before a visitor arrives to read up on subject which interests the visitor. The main lesson in this chapter lies at the heart of this book, and is one that will be repeated later. In essence, think from other people’s perspectives. They are much more interested in their wants and desires than yours.

“Remember that the people you are talking to are a hundred times more interested in themselves and their wants and problems than you are in you and your problems. A person’s toothache means more to that person than a famine in China which kills million people. A boil on one’s neck interests one more than forty earthquakes in Africa. Think of that the next time you start a conversation.”

The sixth and most important principle in this chapter is to make the other person feel important, and do it sincerely. Alluding back to the previous chapter which discussed how every person in the world craves the feeling of importance, the following chapter teaches us perhaps the most important lesson in this book. Always make the other person feel important. Any thing you do to jeopardize their feeling of importance will not be conducive to you finding friends and happiness; that includes showing off, and constant one-upping.

It is the deepest urge in human nature to crave appreciation. Hence, try to find something you admire from every person you meet. Stop acting sanctimoniously and stop being patronizing to those below you.

“A great man shows his greatness by the way he treats little men.”

Making the other person feel important takes little effort, and it is something we can do to spread a little joy to the world. It is wrong to think of it as a way to get something out of other people. As the author puts it:

“If we are so contemptibly selfish that we can’t radiate a little happiness and pass on a bit of honest appreciation without trying to get something out of the other person in return – if our souls are no bigger than sour crab apples, we shall meet with the failure we so richly deserve.”

The unvarnished truth is that everyone you meet feel superior to you in some way. The more you jeopardize that, the more enemies you will make. Therefore, the tact thing to do is to let them realize, in any subtle way, their importance. And do it sincerely!

Part 3 - How to Win People to Your Way of Thinking

The first principle is to avoid arguments all together (for it is impossible to win) The author begins the chapter with an anecdote of him at a dinner party. The host brought up a quote that he thought came from the Bible; He was wrong, and Carnegie knows it. So to acquire a sense of importance and display his superiority, Carnegie appointed himself an unsolicited and unwelcomed committee of one to correct the host.

Actions like these are common and tactless. Although we might have displayed our knowledge or superiority, it accomplishes nothing but ruin the mood, and potentially make the other person dislike your presence. Why tell a man he is wrong in such trivial occasion? Why not let him save his face? He didn’t ask for your opinion, correction, why start an argument?

An argument is almost impossible to win. Even if you win an argument by force, you will never get the other person’s good will. So which one would you prefer? Do you prefer a fleeting sense of importance? Or someone’s good will?

“A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.”

“You can measure the size of a person by what makes him or her angry.”

The book presented another anecdote about an argument between an income tax consultant and a government tax inspector. They argued for hours on end and both side just get stubborn as they went along. By deciding to change the subject and avoid argument, the stalemate ended with the tax inspector backing down. In short, in arguments we get our feeling of importance by loudly asserting our authority or knowledge. Once the argument stops and one side admit the importance of the other side, both side can become sympathetic and more subdued.

The book also offers some suggestions on what to do to keep a disagreement from becoming an argument.

-

Welcome disagreement. If both parties always agree, one of them is not necessary. See disagreement as a potential learning opportunity

-

Avoid the instinctive shift to being defensive and control your temper

-

Listen first. Give the other person a chance to talk. Do not interrupt or correct. Try to build a bridge of understanding rather than building more barriers

-

Look for area of agreement, admit your mistakes if necessary

-

If the disagreement is significant, promise to think over your opponent’s idea. Schedule another meeting later and ask yourself the following question:

- Could they be right? Is there any merit in their position?

- Is my reaction to relieve the problem or to relieve my frustration?

- What would happen if you win, or if you lose?

- Is the disagreement important? Will it just blow over?

The second principle is to respect the opinion of others. Never say “You are wrong.” Stop correcting others needlessly. In fact, remove “you’re wrong” from your colloquial speech. Never begin a conversation or argument by denying the opinion of others outright. It arouses opposition and makes the listener more combative before you even start to be convincing. It is already difficult to change someone’s mind under normal conditions, why make it harder?

“You cannot teach a man anything; you can only help him to find it within himself” – Galileo

“Be wiser than other people if you can; but do not tell them so.” – Lord Chesterfield

“One thing only I know, and that is that I know nothing” – Socrates

If you must do so, try to do it adroitly and subtly so that it will be as if the other person discovered it. It also helps if you can admit your own mistakes first (more on this later). Your honestly will make the other person more open-minded and fair.

“Few people are logical. Most of us are prejudiced and biased. Most of us are blighted with preconceived notions, with jealousy, suspicion, fear, envy, and prejudice. And most citizens don’t want to change their minds about their religion, haircut, communism or their favorite movie stars.”

Sometimes we change our mind without any resistance or thought, but if someone comes along and tell us we are wrong, and how we must change our mind, we become entirely obdurate and unwavering. It is clear that the ideas themselves are not important to us, instead it is our self-esteem which is being threatened.

All in all, there is little to gain and so much to lose when you tell a person straight out that he or she is wrong. You only succeed in stripping that person of self-dignity and make yourself an unwelcomed guest of any discussion.

Benjamin Franklin used to be a direct and blunt fellow who took pleasure in telling others of the contradictions in their arguments. He was insolent and opinionated. Although he was not a fool, he often offended others by his superiority. Ultimately, he realized his mistake and made it a rule for himself to stop all direct contradictions to the sentiments of others. He stopped using words that imported fixed opinions (certainly, undoubtedly) and changed them to softer, more opinionated words like (I imagine, From my understanding). He denied himself the pleasure of contradicting others, and his relations with others greatly improved.

The third principle is to admit your own fault quickly and emphatically. There are many reasons why admitting one’s mistake is advantageous. When we apologize emphatically, the opponent’s only way of acquiring a feeling of importance is to take the magnanimous attitude showing mercy. In addition, having the courage to admit one’s mistake clears the air of guilt and defensiveness, and furthers the conversation along towards a possible solution.

“By fighting you never get enough. By yielding you get more than you expected”

This principle should strike a balance with the necessity of being decisive and not have others take advantage of your vulnerability.

The fourth principle is to begin in a friendly way. When your temper is aroused and you just want to unleash your thoughts by harshly criticizing the other person, ask yourself this: “Yes you will have a fine time unleashing your feelings, but what then? Will your opponent share your pleasure? Will your belligerent attitude foster a cooperative atmosphere?”

The answer is a resounding “No!” Even if you know 100% that the other person is wrong, it is prudent to take a more tactful approach; it will change more mind than blunt criticisms. Beginning in a friendly way is disarming, while the other approach works against your favor.

“The sun can make you take off your coat more quickly than the wind”

“If a man’s heart is rankling with discord and ill feeling toward you, you can’t win him to your way of thinking with all the logic in Christendom. Scolding parents and domineering bosses and husbands and nagging wives ought to realize that people don’t want to change their minds. They can’t be forced or driven to agree with you or me; But they may possibly be led to, if we are gentle and friendly.”

“A drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall. So with men, if you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend. Therein is a drop of honey that catches his heart; which say what you will, is the great high road to reason.”

The fifth principle is to start by seeking mutual agreement and find common ground. The rationale for this principle lies in human psychology. When we say “No” right at the beginning, our brain has already wired itself to remain consistent. You might feel that your “no” is ill-advised later, but your pride is on the line, and no body enjoys admitting fault. As such, we improve our chance of winning others to our way of thinking by bypassing that neurological blockade. Start by getting the other person to say “yes, yes!”. It doesn’t pay to argue, instead we should seek mutual agreement and a cooperative atmosphere which is more conducive to addressing the disagreement.

Instead of beginning with “you should do this.” Try to think of ways in which you and the other person’s interest align, and what sorts of questions can get him/her saying “yes, I agree”. A favorite phrase of mine is: “You are definitely in a precarious situation. I would have acted the same way. (then talk about common goal)”

“He who treads softly goes far”

The sixth principle is to let the other do the great deal of talking. We all care more about ourselves than those around us. So when you are in a conversation with another person, don’t ever interrupt them. Let the other person talk; they won’t be paying attention to you because they still have ideas in their heads begging for expression. The more important idea in this chapter is to avoid showing off and be humble. Most of us would rather boast about our achievements rather than hearing about the achievements of others. When we attempt to show off in front of our friends, that does not make them feel important. It arouses inferiority and envy. A good rule to remember is to never boast about your achievements; only mention them when asked.

“If you want enemies, excel your friends. If you want friends, let them excel you.” – La Rochefoucauld

The Seventh principle is to let the other person feel that an idea is his/hers. The main goal of this chapter is to teach the proper way of getting corporation. It begins with the idea that we have much more faith in ideas that we discovered for ourselves rather than ones handed to you on a silver platter. Therefore, it is prudent to guide the other person to your conclusion without them knowing rather than shoving it down their throat.

“The reason why rivers and seas receive the homage of a hundred mountain streams is that they keep below them. Thus they are able to reign over all the mountain streams. So the sage, wishing to be above men, putteth himself below them; wishing to be before them, he putteth himself behind them. Thus, though his place be above men, they do not feel his weight; thought his place be before them, they do not count it an injury.” -Lao-tse

The eighth principle is to be sympathetic and see things from the others point of view. In our encounters with other people, they may be totally wrong; but they don’t think so. Any fool can condemn and quickly point to mistakes. Only wise, tolerant, and exceptional people even try to understand them. In short, walk a mile in the other person’s shoe before judging them. A excellent strategy when asking others for a favor is to close your eyes, and pause to picture yourself as the other person. Try to understand what they want instead of what you want.

The ninth principle is to be respectful of other’s ideas and desires. The lesson follows closely with that of the previous chapter, which relates to understanding others. Carnegie presents a magic phrase that eliminates all ill-feelings, create good will, and stop the argument.

“I don’t blame you one iota for feeling as you do. If I were you I would undoubtedly feel just as you do.”

The phrase works wonders because you can say it with 100% sincerity, for you really would do the same given the same environment, temperament, physical body, and experiences. The author presents several situations where sympathy made all the difference in arguments, including a fascinating story of a girl with long finger nails that impeded her piano skill development. The teacher, instead of forcing the girl to cut her nail, insisted that she understand that her finger nails were a thing of beauty, and that it would be a sacrifice to get rid of them.

Another great tip presented in this chapter is to wait one day before sending off a critical letter or email. It does not matter how impertinent or severe of a impropriety the person has committed, think things through with a clear mind unaffected by emotions.

“Sympathy the human species universally craves. The child eagerly displays his injury; or even inflicts a cut or bruise in order to reap abundant sympathy. For the same purpose adults… show their bruises, relate their accidents, illness, especially details of surgical operations. Self pity for misfortune real or imaginary is, in some measure, practically a universal practice”

Both adults and children alike crave sympathy. When someone wallow in their self-pity and show their wounds, give them abundant sympathy.

The tenth principle is to appeal to the nobler motive. J. Pierpont Morgan observed that all humans have two reasons for doing things; one that sounds good, and a real one.

An entrepreneur might donate thousands to charity with the motivation of alleviating poverty, while the real reason might be the associated tax benefits. A high-school student might say he wants to attend a far-away university for the profound reason of retracing his grand parent’s food steps, or it might be because he thinks the girls there are prettier. A person might say he got into real estate to earn enough money to buy back his family’s farm land, whereas in reality he might just want to earn money and attain financial freedom; it is simply more expedient and noble to say otherwise.

When we interact with others, tap into the nobler – and often secondary – motivation. For instance, When John D Rockefeller wished for the newspaper to stop publishing pictures of his kids, he didn’t simply order the publisher to do so. Instead, he said “you know how it is, boys. You’ve got children yourself, some of you. And you know it’s not good for youngers to get too much publicity.”

The eleventh principle is to dramatize your ideas. In the culture of extremes and superlatives, merely stating a truth no longer suffices. You really have to dramatize your idea to sell your point. For instance to give a structural engineering example, instead of saying: “The floor plate will bear 2.4 kPa of live load, which is more than enough”, say instead: “we can fit two elephants between each column bay and the floor will still hold.”

The twelfth and last principle is to throw down a challenge. Everyone loves the chance to excel. An infallible way to appeal to other people spirit is to throw down a challenge.

“That is what every successful person loves: the game. The chance of self-expression. The chance to prove his or her worth, to excel, to win. That is what makes footraces and hog-calling and pie-eating contests. The desire to excel. The desire for a feeling of importance.”

Part 4 - How to Be a Leader

The first principle is to begin with praise and honest appreciation. The psychology of this technique is simple: It is easier to listen to unpleasant things after hearing our good points first. Therefore, begin with praises like a dentist who prep his patients with Novocain. A drilling happens either way, but one is obviously better.

In applying this principle, many people opt to use the phrase: “you were [praises], but …” which is ineffective. The “but” makes the other person question the sincerity of the first statement. Rather, we should switch “but” with “and”. For instance, compare the following two phrases.

-

“You were excellent in math class, but you should also focus on English”

-

“you were excellent in math class, and if you applied the same effort, you will be just as excellent in English class”

The second principle is to call attention to others mistake indirectly. This technique has been profoundly influential in my life. For the past few years, I was never tact enough to realize how the other person’s feeling of importance might’ve been robbed. No one likes the embarrassment or the feeling of incompetence of making a mistake. Therefore, employ methods to point out mistakes indirectly, like asking questions, or praise before you criticize.

The third principle is to talk about your own mistake before criticizing other’s mistake. This principle can be applied when the other person must be made aware of their mistakes, and that there is no other way other than criticism. Admitting our own mistake lowers the guard of the other person, and establishes a friendlier atmosphere. You are signaling to the other person that there is no perfect human being and that everyone makes mistakes.

The author gave an example of his underperforming young secretary, who was his niece at the time. Instead of criticizing outright, Carnegie was a lot more tact:

You have made a mistake Josephine, but the lord knows, it’s no worse than the many I have made. You were not born with judgement. That comes only with experience, and you are better than I was at your age. I have been guilty of so many stupid, silly things myself, I have very little inclination to criticize you or anyone. But don’t you think it would have been wiser if you had done ……”

The fourth principle is to ask questions as a means of giving orders or pointing out mistakes. This principle works in a comparable manner as the previous one. When we say: “would this work better?” instead of “Do this instead.” It makes it easy for a person to correct himself. It saves the other person’s pride. It encourages cooperation instead of rebellion.

A man capable of being a leader must be decisive and straight forward; however, sometimes it pays to phrase the order in the form of a question.

The fifth principle is to let the other person save face. Most people don’t ever stop to consider the pride and dignity of others. By being more sympathetic and considerate of other’s view point, we can become more tactful in our daily dealings. Even in situations where the other person is definitely wrong, we only destroy ego by making someone lose face. Instead, we should do whatever is in our power to save the dignity of the other person; which is a product of being more sympathetic.

The sixth principle is to praise any slight improvement. The theory is applied frequently in child rearing. Encouragement and praise is usually more effective than criticism. We are often ready to apply criticism, but are reluctant to provide recognition. For better results, it is prudent to be as specific as possible. When we single out a specific accomplishment, the praise becomes more meaningful and sincere. A general praise may sound like too much like a flattering remark.

The seventh principle is to give the other person a fine name to live up to. In essence, if you want someone to improve a particular trait, act as if that trait is already one of his or her quality. They will make prodigious efforts rather than see you disillusioned. As Shakespeare penned: “Assume a virtue, if you have it not.”

The eighth principle is to make any fault seem easier to correct. A leader cannot appear neurotic and unsure of the best course of action. And when something goes awry, a leader should provide encourage and reassurance rather than panic. If you tell your employees, child, or spouse that he/she is stupid and is doing it all wrong, it removes all incentive to improve. On the other hand, if you make the fault seem easy to fix, you restore the other person’s faith and he will practice until dawn to excel.

The ninth principle is to make the other person happy of doing what you suggest. Sounds impossible, but it really is quite simple. Here is a six-step procedure to be more tactful and make the other person happy to do what you want:

-

Be sincere. Think about the other person’s benefit and forget about the benefits to yourself

-

Be empathetic. Know what the other person planned course of action and what they really want

-

Align interests and seek mutual benefits. Seek benefits that the other person will receive following your suggestions. Match these benefits with their want.

-

Make your request that emphasizes the benefit the other person will receive

Comments